The Seeker

Post-NFL, Ricky Williams has been everything from TV host to spiritual healer. Can the record-setting running back ever stand still?

John Bianco has a favorite Ricky Williams memory. In it, they're both on the verge of tears.

Bianco, the Longhorns’ associate athletic director for media relations, had helped Williams craft a number of acceptance speeches during his college career. The two-time All-American, two-time Doak Walker Award winner, 1998 Walter Camp Player of the Year, 1998 Maxwell Award winner, and 1998 AP College Player of the Year had given a lot of speeches, but in Bianco’s recollection, his Heisman Trophy acceptance speech was the one that brought tears to the eyes of nearly everyone in the room.

“We get on the elevator, and I’m like, ‘Man, you won it. I can’t believe it,’” Bianco says. “It was a great moment for both of us. But he’s got his head down and he’s pouting, and he says, ‘I’m so sorry. I forgot to thank you.’ I didn’t even notice, but that was the first thing that crossed his mind when he saw me after he achieved the crowning jewel of his life.”

Loyalty has always been an important thing to Williams. You might not know it, however, if your primary impression of him came from the cartoon that was created during his troubled NFL career. Fans who still strongly identify Williams as the player who missed a number of games in his early seasons due to injury, faced suspension for drug use, and retired for a year in 2004 to travel the world have long been keen on branding him as selfish.

Mike Bianchi of the Orlando Sentinel branded Williams “The Quitter” in a 2005 editorial, declaring that the “pot-smoking, duty-shirking” Williams had “ruined a season” for the Miami Dolphins. Bianchi was hardly Williams’ only critic. A 2011 list of “The 10 Biggest Quitters In NFL History” gave Williams its No. 2 slot; a Los Angeles Times slideshow of “Pictures of the Biggest Quitters” features his portrait; a 2008 story from ESPN mocked him as “a disgraced hero slogging his way through the ridicule and the doubts.” As recently as this August, Williams caught flack for making an offhand comment about Texas A&M quarterback and fellow Heisman winner Johnny Manziel. “Once you win the Heisman, there’s going to be more attention on you,” he said. “You are probably not going to be able to get away with all the stuff you got away with before.” The comments sections of sports websites filled up with responses like, “Says the guy who quit on his team,” and “Ricky should smoke some pot and shut up.”

Those fans are unlikely to be moved by Bianco’s story of a tearful Williams, ashamed that he forgot to thank his mentor. But Williams—a media-shy star who self-financed a documentary about his own life, and a punishing athlete who appeared on the cover of ESPN Magazine in 1998 wearing a wedding dress—has always invited people to consider his contradictions. How else do you describe a football player whose college career was outstanding, but whose time in the NFL mixed both crushing lows (failed drug tests, surprise retirement, and injuries) and brilliant highs (in 2002 he was the league’s rushing leader, first-team All Pro, and Pro Bowl MVP)?

Williams has always been hard to pin down as a personality, and even the documentary that he commissioned about his time away from the game, Run Ricky Run (which aired in 2010 as part of ESPN’s 30 For 30 series), feels like a portrait of who he was at various times in his life, rather than a singular take on who he really is. Ultimately, Williams still seems restless, constantly pursuing different avenues for his passions. You can’t blame his critics for not having a clear idea of who Ricky Williams really is—even Williams himself has spent a lot of time trying to figure out the answer to that question.

But now, at 36 years old and settled in Austin, one thing Williams does know is that—despite a quixotic NFL career that left fans and columnists questioning whether he even liked the game—whoever he is, he’ll always be a guy who loves football.

On a hot July afternoon, Williams is at Hyde Park Bar & Grill for lunch, and the waitress is flustered. She never says anything that gives away the fact that she recognizes him, but her demeanor betrays her—she hadn’t been stammering before he pulled up in a Jeep Wrangler, but suddenly “Can I get you something to drink?” is a tough question for her to get out. When he responds with, “I’ll take a beer,” she says, “OK!” before sheepishly returning seconds later to ask him what kind. He’s very friendly—a waitress could do a lot worse for a customer—but he’s still Ricky Williams, and this is still Austin.

Williams has been back in Austin since he retired from the NFL at the end of the 2011 season. On weekends, and sometimes on Monday nights, he plays softball. On Tuesdays, it’s flag football. Williams is still in superb shape, and it’s hard to imagine lining up against him in a friendly game of flag football in an East Austin park (he plays defense). But the 1998 Heisman winner and 2002 Pro Bowl MVP doesn’t worry about it much. “It’s fun, because the people I play with, half of them are starstruck, and the other half wants to prove that they can compete against an NFL football player,” he says, laughing.

It’s hard to square the guy gushing about how much fun he has playing with the stereotype of a disaffected pothead who, when forced to choose between playing football and getting high, chose to keep getting high. And if that comes as a surprise, just wait until you hear what he’s doing professionally.

A quick glance at his résumé indicates that, whoever else he might be, Ricky Williams is a seeker. His quest to find fulfillment has led him to try things that many pro football players are likely to laugh at. There aren’t many recently retired NFL veterans who are licensed massage therapists, or who have spent time as yoga teachers or running self-help workshops.

Williams runs a traveling workshop series called “Ricky Williams: Accessing You” that puts him in a room with a small group of participants for five days, helping them to reach their potential. Attendees are mostly women, though he says his football background attracts some men who might otherwise shy away from a self-help seminar. He travels the world with the workshops; this summer he was in Melbourne, Los Angeles, and San Francisco. They often take place in hotel ballrooms with bad carpeting and involve sitting in chairs as Williams and a co-facilitator explain ideas about “access.” At one point, Williams and the other seminar participants lay hands on a subject’s head.

But somehow, given Williams’ reputation as an iconoclast with a new-age streak, those things are easier to believe than his reignited passion for football. Two years after his NFL retirement, Williams is excited at the prospect of being more involved with the game.

In between bites of lunch—which he scarfs down quickly—he’s eager to discuss an experience he recently had in Australia. “I was asked to go to a football game. I went to their practice and actually installed a play,” he says, explaining that the Australian passion for football—they call it “gridiron”—is diluted by their affinity for rugby union and Australian rules football. “I have this urge to be an ambassador with football. I love to travel, and I think football’s an amazing brand,” he says. “I have a lot of knowledge to share.”

That is something that anyone who has ever spent much time with Williams seems to agree on. “What sometimes gets overlooked with Ricky is how intelligent of a football player he was,” Texas head coach Mack Brown says. “He’s just a brilliant guy with a bright football mind.”

These days, he’s using his football mind in more ways than one. He is interested in pursuing some sort of formal ambassador relationship with the NFL to bring the game to other countries, but he’s also sharing his knowledge on television and on the field. After some limited work as a broadcaster with the Longhorn Network last season, Williams surprised himself by expanding his role for the 2013 season. “Last year, we said, ‘Whenever I’m open.’ This year, if there’s a game, I’m going to do a game,” he says.

In addition to broadcasting, Williams has also dipped his toe into coaching—but while he’s interested in working with players on the field, Williams’ years of pushing himself have taught him that his initial enthusiasm can quickly leave him bored and burnt out, and he doesn’t want to overcommit.

“There’s this program that came up through the NFL Players Association where they give you a coaching internship. They match you with a school where there’s a need,” he says. Williams considered applying, but didn’t want to stretch himself too thin. “It would have been all of my time, and they would have sent me to New Jersey,” he laughs. Instead, he made some phone calls and landed an opportunity to be an assistant running back coach at the newly launched program at the University of the Incarnate Word in San Antonio. It seems like a better fit. “Whenever it fits into my schedule, I’ll be down there coaching their running backs,” he says. “For me to be able to do Longhorn Network and also do a little bit of coaching during the season—that seems like a lot of fun.”

When I ask him if he’s trying all of these things because he’s hoping to fall in love with something, he smiles, shakes his head, and gives one of those open-book answers that makes him equally endearing and frustrating. “I’m hoping to fall in love with everything I do,” he says. “I used to think I was going to find that one thing that was going to make me happy, and I found it, and it made me happy for 10 seconds. So now, I just embrace that I know that I’m going to find things that I’m going to love, and I know that I’m going to get bored of them quickly, too.”

The people who have known him the longest don’t find this aspect of his personality frustrating—if you’re really good at everything, maybe you should try, well, everything. “Ricky’s not a guy that I worried about whether or not he’d have success after his football days were up,” Brown says.

“He’s one of those guys you don’t want to set boundaries on,” Bianco agrees. “He obviously could make it as big as he wants, as far as broadcasting. He’s still got a lot of years left, and I can’t even imagine where it’ll ultimately end up.”

Williams—football player, broadcaster, coach, massage therapist, yogi, and spiritual healer—probably can’t predict that either. Ultimately, it seems like he’s content to keep searching. “Whenever I saw a field, I wanted to go run around,” he says of his childhood, but he also drops lines like, “I kind of feel I wasn’t supposed to be an athlete,” over lunch. He cites his yoga and massage practice as the reason why he’s the very rare 36-year-old former NFL running back who wakes up without pain.

But rather than let that make him a contradiction, Williams still seems very interested in proving he’s capable of containing a love for yoga, football, spirituality, broadcasting, and more—all at the same time. When I mention that, in the movie version of his life, his career would have ended with him playing one more season in Baltimore to hoist the Super Bowl trophy with the team last February, he corrects me: “In my version, it would end with me winning the Nobel Peace Prize.” Williams may not give people a clear idea of exactly who he is, but he’s very clear about who he isn’t. He’s not your stereotypical dumb jock, and from the yoga to the dreadlocks to the world traveling, he’s been eager to make sure other people’s shallow notions of what he’s supposed to be won’t define him.

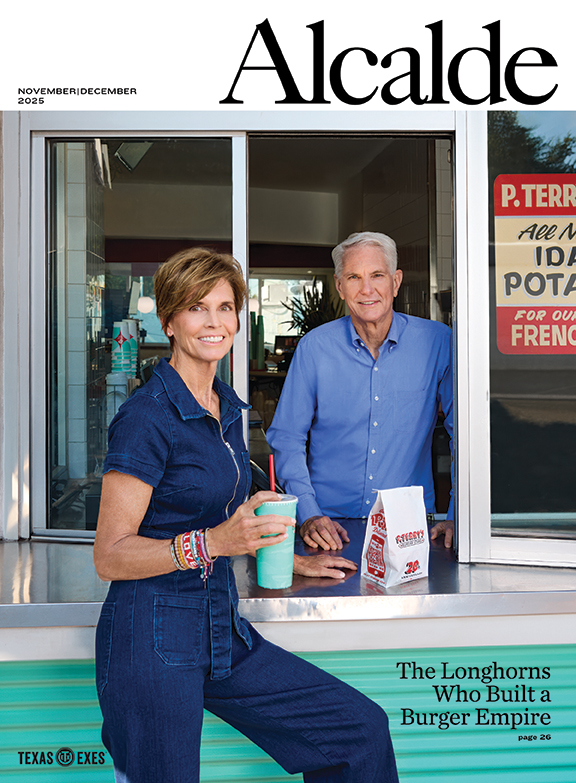

And so while he loves the game, it also wouldn’t be the world’s safest bet to assume that Ricky Williams’ story ends with him on a football field, blowing a whistle or holding a microphone. Football gives him the opportunity to chase other interests—teaching, public speaking, traveling—but the part of him that is a seeker is excited about every other option out there, too. “When I die, in my obituary, I want that I played football to be one little line at the bottom,” he says. “‘Oh, yeah, he was a football player, won the Heisman Trophy.’ I want the life that I live to be so rich that it’s just something that adds to the story.”

Photos from top:

Ricky Williams looks over his display booth before the induction of the 2013 class of the Texas Sports Hall of Fame in Waco. AP Photo/Waco Tribune Herald, Jerry Larson.

Illustration by Jeffrey Smith. Photo by Jim Sigmon.

Williams and John Bianco at the 1998 Heisman Trophy awards ceremony in New York. Photo courtesy UT Athletics.

Williams practices massage and holistic healing. Photo by Michael Francis McElroy/ZUMA Press.