Fightin’ Words

Too many writers and outsiders make a mockery of Texas. Don Graham says those are fightin’ words, and explains why we should celebrate, not satirize, our state’s culture.

Defending Texas culture is a full-time job. I know because I’ve been teaching and writing about Texas culture for four decades and counting. I never planned it that way. After completing a Ph.D. in American literature from UT in 1971, I went off to teach at the University of Pennsylvania, where to my surprise, they saw me as a cowboy and wanted me to teach a course in Western movies, which also surprised me. I had seen hundreds of Western movies in my youth but had never thought about them as subjects for academic study. But being a Texan in the East, one could not escape the cowboy connection, though my own Texas roots were more Southern than Western. In the Collin County I grew up in, cotton was king, farmers rather than ranchers dominated the economy, and there was no romance in plowing behind a mule (or riding a John Deere tractor).

Defending Texas culture is a full-time job. I know because I’ve been teaching and writing about Texas culture for four decades and counting. I never planned it that way. After completing a Ph.D. in American literature from UT in 1971, I went off to teach at the University of Pennsylvania, where to my surprise, they saw me as a cowboy and wanted me to teach a course in Western movies, which also surprised me. I had seen hundreds of Western movies in my youth but had never thought about them as subjects for academic study. But being a Texan in the East, one could not escape the cowboy connection, though my own Texas roots were more Southern than Western. In the Collin County I grew up in, cotton was king, farmers rather than ranchers dominated the economy, and there was no romance in plowing behind a mule (or riding a John Deere tractor).

Maybe it was something about the way I walked or talked that made everybody in Philadelphia think I was a cowboy. Certainly my colleagues at Penn did. Late one afternoon as I was walking down an empty corridor of the building that housed the English department, a soon-to-be-famous scholar of African-American literature (Houston Baker, Jr.), upon seeing me coming his way, went into a crouch and did a fine impersonation of a gunfighter drawing a Colt .45 and blazing away at my no doubt slouching Jack Palance languor. In those days it was open season on Texans on the East Coast. It still is. We’re all cowboys; we’re all, deep down, Confederates; and we’re all a little bit dumb.

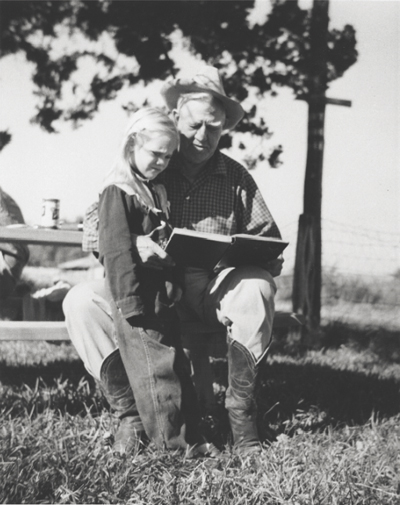

J. Frank Dobie with Caroline Wardlaw, Cherry Springs Ranch, Summer 1955.

The way things fell out, I returned to UT to teach Western movies and to take up the mantle of J. Frank Dobie’s famous course, E342, Life and Literature of the Southwest. The E was styled on its back, like a brand; the lazy E, as Dobie called the course in 1940. An irony that I’m not sure Dobie would have appreciated is that my Texas—North Central blackland prairie cotton country—was as different from his brush-country South Texas ranching culture as could be. Fact is, Dobie was never much interested in anything east of I-35. In any event, at UT I was considered a cowboy just as I had been at Penn. That’s because most of the UT English department hails from parts elsewhere: East Coast, Midwest, California—all sites of superior attainments compared to dusty old weather-beaten backward proud arrogant Texas that had once been a Republic and wouldn’t let anybody forget it.

Long ago I ceased trying to explain the difference between Collin County, where I grew up, and Archer County, where Larry McMurtry grew up—that is, between a cotton farm and a cattle ranch. These days many of my students routinely confuse the two terms, having been born and raised in cities, thus reflecting the dominant statistics of the state’s demographics for the past 20 years or so: about 82 percent urban, 18 percent rural or small town. Also, most of my students have no idea who J. Frank Dobie was, and now an increasing number have never heard of Larry McMurtry either. So there remains much to do in the class, to create a sense of a dynamic literary culture before it all gives way to the fog and obscurity of total oblivion of place and past.

As a sample of the current antipathy to all things Texan, I cannot do better than quote from the valedictory of the most recent editor of the Texas Observer, the little progressive rag that has been published in Austin since 1954. Over the years, under various editorships, the Observer has gone through spasms of progressive ire directed at Texas, and currently the magazine has been in a state of wrath for several years. In editor Bob Moser’s last column, in August, he wrote of how he came down here to head up the magazine despite his “skeptical East Coast friends.” Here, he said in a nod to down-home rhetoric, he would do “the Lord’s work”—which in his case meant making mincemeat of Texas culture. That task completed, he is leaving to go “back east for another job at another national publication,” but he couldn’t resist exhorting his readership one last time: “Keep your eyes on the prize, people—on the new Texas that will dawn, over the next couple of decades, as the hoggish Anglo majority that has built the meanest and most unjust state in America finally, justly, becomes inconsequential (emphasis added). That’s us, folks, or many of us. I say go on back to New York City, I do believe I’ve heard enough.

Among my heroes of championing Texas culture I would mention two in particular. One is John A. Lomax, who served as editor of The Alcalde in the early years of the Alumni Association, which became the Ex-Students’ Association. Back in 1895, just a dozen years into the intellectual life of the University, Lomax, a first-year student, brought a manuscript of his to the attention of his Shakespeare professor. It consisted of cowboy songs that he had compiled while growing up in Bosque County, West Texas. He wanted to know what a learned man thought of it. The professor referred him to Dr. Morgan Callaway, Jr., a Johns Hopkins Ph.D. who had written such studies as “The Absolute Participle in Anglo-Saxon” and other esoteric tomes. In his autobiography Lomax vividly records what happened:

I handed Dr. Callaway my roll of dingy manuscript written out in lead pencil and tied together with a cotton string … Alas, the following morning Dr. Callaway told me that my samples of frontier literature were tawdry, cheap, and unworthy. I had better give my attention to the great movements of writing that had come sounding down the ages. There was no possible connection, he said, between the tall tales of Texas and the tall tales of Beowulf.

Fortunately Lomax had grit, and in 1910 he published Cowboy Songs and Other Frontier Ballads, which became an American classic.

Another Texan of that time who had grit was Dobie. He and Lomax were friends; in fact, Dobie worked as a secretary for Lomax in publishing The Alcalde. Dobie himself has recorded how Lomax’s book gave him the idea of doing for cowboy stories what his friend had done for cowboy songs: to collect them, write them, preserve them, and to hell with the old dons who would deny their legitimacy. Although these PhD professors taught in Texas, at Texas, they didn’t recognize Texas itself as a legitimate site of literature or culture. Literature and culture lived elsewhere, in England, in New England, but not here in Texas.

When Dobie proposed then, in 1929, to create a new course at UT to be called Literature of the Southwest, the professors in the English department reacted predictably: they rejected outright the premise that there was such a thing as literature of the Southwest. Dobie, as stubborn as Lomax, retorted famously, “All right, there is plenty of life, I’ll teach that.” And teach it he did for over a decade, and the course has remained on the books. 2011 is the 81st year of its existence. May it hoggishly continue.

Speaking of hogs, an excellent example of another thing that Texans have to put up with is novels about our fair state that lampoon us or otherwise misrepresent us. Annie Proulx, a celebrated novelist, set her 2004 work, That Old Ace in the Hole, in the Panhandle. The novel’s plot is about a representative of Global Pork Rind named Bob Dollar who comes to the Panhandle to promote pig farms. Proulx herself spent six months living in the Panhandle, presumably to get the atmospherics right, and she met a lot of nice people, she tells us in a brief foreword.

Yet in the novel none of this reality comes through. What we get instead are ridiculous caricatures starting with the names of her characters. Here is a partial list from scores of such in the novel: Ribeye Cluke, Rope Butt, Harry Howdiboy, LaVon Fronk, Wally Ooly, Hen Page, Cy Frease, Freda Beautyrooms, and Dick Head. All of these folks can be found in the West Texas town of Woolybucket.

But wait, these characters speak, too, and in Proulx’s rendering of Texas talk she scores a thousand on the stupid scale. They say “Graindeddy” instead of Grandaddy, and they say “crik” instead of creek. Sure they do. But the kicker is this: they say “homaseashells” to describe a particular orientation. I tell you, that Annie Proulx is a card.

It doesn’t have to be this way. Cormac McCarthy, for example, born in Rhode Island and raised in Tennessee, brilliantly gets the places and the language of Texas right. In No Country for Old Men, for example, the story is grounded in real places with real names, Sanderson and Dryden in Terrell County, out by the Rio Grande. And the characters have real-sounding names: Ed Tom Bell, Carla Jean Moss, Carson Wells. The only one with a strange name is a very strange man indeed, the “ultimate bad ass,” Anton Chigurh. And if you want to hear Texas vernacular rendered in perfect pitch and cadence, just read any page of the novel, and you’ll hear it. “You can’t salt salt,” Sheriff Bell says, and you can’t sell us a fake Texas, either.

Here’s a rule of thumb: Any time you read a novel set in Houston and there are tumbleweeds tumbling through the city, you know you’re in faux Texasville.

Adam Braver’s take on the Kennedy assassination in his 2008 novel, November 22, 1963, shows how a predisposed view of Texas can lead the novelist to distort even the smallest facts. A native Rhode Islander, Braver was born in 1963, so his novel has to be the fruit of research rather than of on-the-ground experience. In an early scene he describes Jack and Jackie their last morning together, in their room at the Hotel Texas in Fort Worth. They are looking at rare European paintings placed on display for their pleasure by the good people of Fort Worth. The point of view is Jackie’s: “They may hang cow skulls from every spare nail in this state, but when it comes to taste, even the Texas socialites turned to the Europeans.”

This is called snobbery, and Jackie Kennedy was a snob. Braver could have stuck to the facts, but then he couldn’t have revealed his own biases. What really happened is that both the president and his wife were touched at the thoughtfulness of those socialites who had arranged for the paintings (borrowed from Fort Worth art galleries) to be placed in their room. In fact, JFK looked up the name of one socialite and called her to thank her for her kindness. That’s what happened.

In Australia there’s a long-standing phenomenon called the “cultural cringe.” The phrase describes the subservient status of a colonial outpost to the superior, imperial culture of Great Britain. Texans should avoid succumbing to the cultural cringe, to pulling our forelocks in the presence of supposedly august personages from the East Coast. Often our books get overlooked by local press, especially in Austin, where any New Yorker writer who claims to be an expert on barbecue receives accolades, while native sons and daughters get overlooked and their books go unreviewed. I’ll leave the last word to J. Frank Dobie: “If people are to enjoy their own lives, they must be aware of the significances of their own environments. The mesquite is, objectively, as good and as beautiful as the Grecian acanthus…We in the Southwest shall be civilized when the roadrunner as well as the nightingale has connotations.”

Photo by Matt Wright-Steel.

5 Comments