It's almost noon on the Snake River,

and Shawna* has a bite. Thirteen years old with wavy cinnamon hair, a smattering of freckles, and a resolute gaze, she’s been standing in a little gray fishing boat for four hours, her wrist flicking back and forth as she casts her rod again and again to no avail. Jim Hickey, a former professional fly fishing guide, steers the boat toward advantageous spots and offers encouragement: “You got this, girl!” This stretch of cold, pristine water is teeming with trout, but none of them have been tempted by the gold stonefly nymph at the end of Shawna’s line.

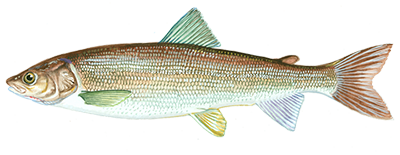

But now the line jerks and tugs, and Shawna’s green eyes widen as she reels it in. Hickey plunges his hand into the river and holds up her prize: a flopping five-inch whitefish. “Just a whitey,” he announces. Most fishermen turn their noses up at whitefish, a common and homely species, but Shawna’s still smiling. “Oh well!” she says cheerfully. The fish goes back in the water, and with a shake of her head, Shawna

starts casting again. She’s in no hurry. Even though she’s never fly fished before today, she already seems to grasp one of the key tenets of the sport: There’s only so much you can control. The river brings you what it wants, and all you can do is enjoy the ride.

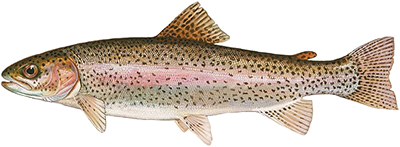

Irwin, Idaho, pop. 222, is a dot on Highway 26 an hour east of Idaho Falls. The town has an ice cream stand, two restaurants, and a gas station called Huskey’s, where you can rent a log cabin right in the parking lot. It’s also nestled between two spectacular mountain ranges, the Caribou and the Big Hole. Snow-capped peaks give way to lush alpine forests lining the riverbanks, and in the brief but glorious summers, the hills erupt with yellow wildflowers. It’s hard to pass an hour without a wildlife sighting: the Swan Valley is home to bears, wolves, marmots, moose, elk, ospreys, eagles, and bountiful trout that make for some of the best fly fishing in the country. Each mile of the Snake River boasts more than 5,000 fish, many of them the big, colorful rainbow and cutthroat trout that fishermen’s dreams are made of. That’s what first brought Steve Davis here. “I love this place,” he says. “There’s nowhere else quite like it in the world.”

He hopes that, in some small way, fishing can help them heal, the way it healed him.

At 59, Davis, BBA ’78, is a soft-spoken man with a youthful face, ruddy cheeks, and close-cropped white hair. He’s the founder of a fly fishing camp called On River Time. For one week each summer, he and his team bring a small group of teenagers to a luxury lodge in Irwin for a week of fishing and fun. Over long days on the water, they master the art of casting and mending, of tying flies and studying the current. In the evenings they fish some more, play touch football, or sprawl on the grass and talk about their favorite video games, their celebrity crushes, their hopes and dreams—typical teenager discussions. But they are not, in fact, typical teenagers. They are all survivors of child abuse, neglect, or human trafficking. They have felt and sometimes still feel the deep-seated shame and hopelessness that can remain long after the abuse is over. Davis understands this better than most. And he brings them here because he hopes that, at least in some small way, fishing can help them heal, the way it healed him.

Steve Davis, BBA '78, fishing on the Snake River behind the Lodge at Palisades Creek.

When Davis was growing up in Kirbyville, Texas, in the 1960s, everybody knew everybody’s business. This was partly because of the familiarity inherent in small-town life, and partly because the telephones were still on a party line. “We shared the line with five or six families,” he remembers. “Everyone had their own ring. Three short rings meant the call was for us.” Often, at a pause in the conversation, Davis could hear the breathy static that meant someone was eavesdropping.

Davis spent most of his time outside. “You either made your own fun or you did chores,” he says. His father worked shifts at a paper mill, while his mother stayed home with him and his younger brother and sister. The family always seemed to be just scraping by, even with a small farming operation on the side. Davis’ chores included feeding the cows, picking beans in the garden, and mowing four acres of grass with a perpetually broken mower. When adults asked what he wanted to be when he grew up, he answered, “A traveling man,” although he wasn’t sure exactly what that meant. He only knew he wanted to see the world. “My dream from the time I was 8 years old was to just get on our horse and ride out of town,” he says.

It was a hardworking childhood, but a happy one. Davis loved school and did well in it, and his parents cheered him on. He played on the football team. There was never any question that he would make it to college, even though no one else in the family had and it wasn’t clear where the money would come from. And he speaks fondly of what it was like to be a free-range kid: “We had 1,000 acres, a treehouse, and a BB gun.”

He also had a secret. Starting when Davis was in preschool and ending when he was in fourth grade, a relative sexually assaulted him several times. He didn’t have a word for what had happened, but he felt deeply confused, scared, and ashamed. “I remember just not knowing what it was,” he says, “and blaming myself.” Night after night, he would wake in a cold sweat after reliving the abuse in his dreams.

He resolved never to tell anyone. “I buried it as deep as I possibly could and it stayed there.”

Irwin, ID

Irwin, ID

Snake River Cutthroat Trout

Snake River Cutthroat Trout