The Scientist

Live Oak Brewing Company

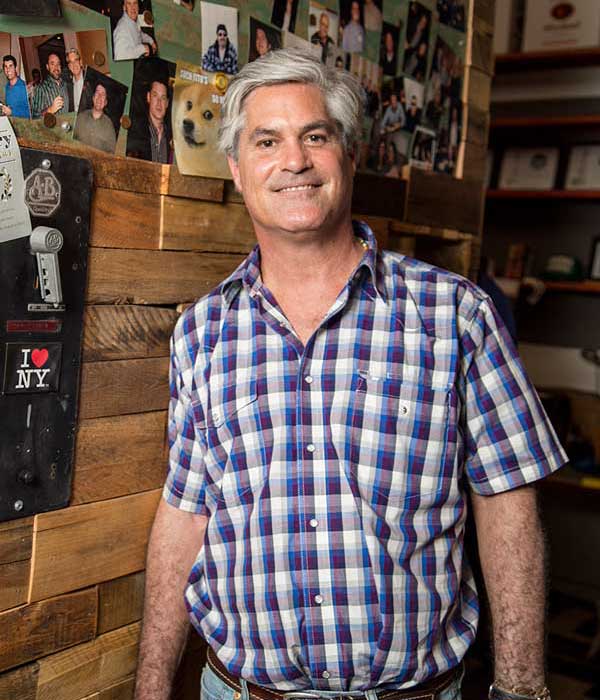

Founder: Chip McElroy, BA '79, PhD '89

Known for: Authentic, old-world-style beer

Beer to try: Live Oak Hefeweizen

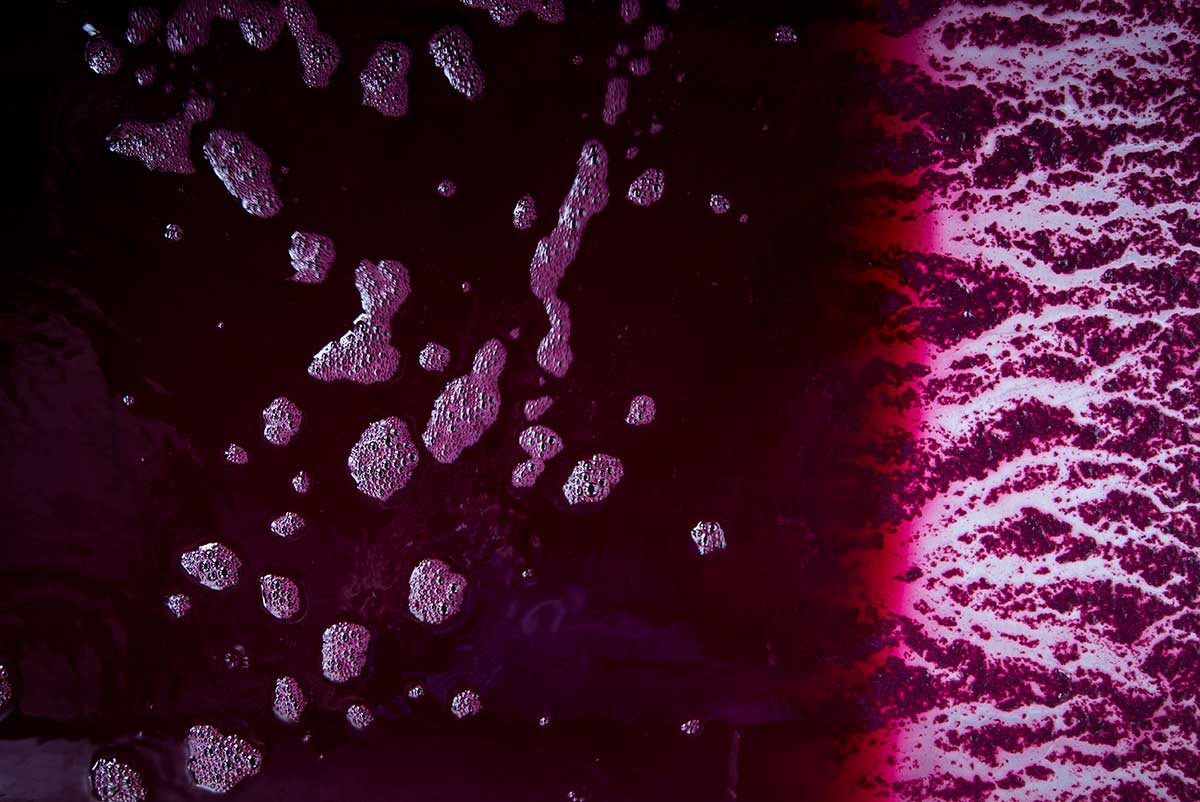

Sitting in the Live Oak Brewing Company biergarten recently, with small, crisp leaves falling all around us, founder Chip McElroy is making a point about authenticity. He’s explaining why, for example Live Oak uses a complicated decoction mash, mostly imported hops, and horizontal fermentation to make his award-winning pilsners and European-style lagers with expensive German-engineered equipment.

“It would be like if I had bratwurst and sauerkraut on the menu,” he says, “and I brought you out a hot dog and some coleslaw.”

This is to say that McElroy takes beer very seriously. It started on a Czech bicycle and brewery tour in 1995, when he quickly realized that the outing was more bike than beer. He ditched his ride and took himself on a self-guided brewery tour, knocking on doors and asking brewers how they made pilsner. To his surprise, most were incredibly helpful.

In 2014, there were 117 craft breweries in Texas. In 2015, there was a 60 percent increase to 189, its largest jump ever. When McElroy opened in a former meatpacking plant in East Austin in 1997, there were four: Real Ale, Saint Arnold, Celis, and Live Oak. Back then, McElroy says, all the U.S. craft breweries were making pale ales. But he wanted to replicate those same beers he drank in Europe, like Pilsner Urquell, so he imported an heirloom variety Czech malt and brewed the same way the Europeans were. When I ask him why he goes through the trouble and avoids recent beer trends, he’s succinct.

“Because they’re delicious,” he says, as if I’ve asked him why he breathes oxygen. “It’s simple. They’re delicious beers.”

And with a background in chemistry and homebrewing and the gumption to learn tried-and-true European brewing methods, he was essentially working with a stacked deck.

“We were brewing against adversity, but we were making very clean lager beer,” McElroy says. “It’s difficult to make correctly. We were doing more sophisticated brewing than other brewers were willing, able, and maybe knowledgeable to do.”

For the better part of the next two decades, enormously popular beer like the Live Oak Hefeweizen and the rest of the Live Oak brand of beers were available only on tap at your favorite local watering hole or by the cup at a keg party. Realizing the potential in retail sales and desperate to leave the sausage plant, Live Oak set up a taproom and biergarten out by the Austin Bergstrom International Airport, and on Jan. 15, 2016, started selling cans of Live Oak Hefeweizen in stores. Since then, Big Bark and Pilz have hit shelves around the state.

Sitting inside at the largest double-live-edge live-oak bar in the world, we sip from Live Oak’s portfolio: a resurrection of a formerly extinct Polish beer called Grodziskie, a smoked version of his Bavarian-style Oaktoberfest, and, of course the hefeweizen, McElroy’s best-selling beer. He mentions hints of banana and clove in the latter, and as I throw back my tasting-glass, my neophyte palate is overwhelmed with just that. It turns out that annihilating taste buds with ridiculously over-hopped IPAs isn’t the only way to succeed in the craft beer business.

“We aren’t participating in the IBU [International Bitterness Units] war or the alcohol-strength-war,” McElroy says, smiling. “We’re participating in the delicious beer war.”