Playing the Long Game

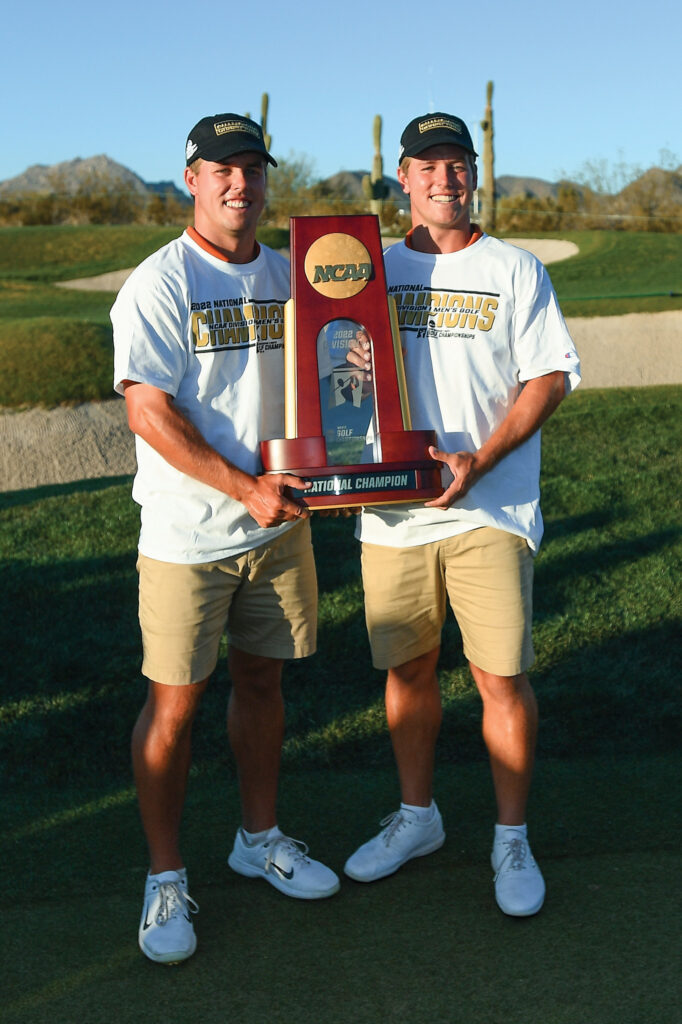

“That’s good.” It only took two words for The University of Texas men’s golf team to win the 2022 NCAA Championship. Junior Travis Vick’s potential clinching two-putt on the 18th hole at Grayhawk Golf Club in Scottsdale, Arizona, had both the pace and position for a likely tap-in, prompting the concession from Arizona State’s Cameron Sisk and …

… burnt-orange pandemonium.

But what took no more than a second on the golf course took a lifetime for coach John Fields and UT’s top five golfers: then-seniors Parker Coody, BS ’22; Pierceson Coody, BS ’22; and Cole Hammer, BS ’22, and then-juniors Vick and Mason Nome. Or rather, the past four years had enough birdies and bogeys—both metaphorical and actual—to feel like a lifetime.

When the Coodys (who are fraternal twins and the grandsons of 1971 Masters Tournament winner Charles Coody) and Hammer (who committed to Texas when he was 14 and qualified for the U.S. Open at 15) arrived as freshmen in the fall of 2018, everything was as it should be. Perhaps even ahead of schedule. In the spring of 2019, a young but loaded Longhorns team that also included Steven Chervony, BA ’19, and Spencer Soosman, BS ’20, went on a magical NCAA tournament run, knocking off both Oklahoma and Oklahoma State in match play before losing the championship to Stanford.

But no problem, right? With Soosman coming back, plus two more top recruits arriving in the form of Vick and Nome, these Longhorns were bound to win a ring—or two, or three—before joining the likes of Jordan Spieth, ’12, and Scottie Scheffler, BBA ’18, on the PGA Tour. After all, this is The University of Texas. The program built by coaches Harvey Penick and George Hannon, with such glittering alumni as Ben Crenshaw, ’73, Life Member; Tom Kite, BBA ’03, Life Member; Mark Brooks, ’83; and Justin Leonard, BBA ’94, Life Member. The program where Fields, the coach since 1998, won his first national championship in 2012 with a team featuring Spieth, Dylan Frittelli, BA ’12, and Cody Gribble, BS ’13. The current players, being as young as they are, grew up rooting for the likes of Tiger Woods and Rory McIlroy on the pro circuit. But once they get into the UT locker room, with its plaques and staff bags commemorating all the Horns who went on to the PGA Tour, they felt the weight of history and possibility.

It’s not just about getting an education and furthering that pathway to the pros. You come to play golf at UT for a chance to win a championship. As Pierceson Coody says with a little laugh: “Coach doesn’t shy away from letting you know why you go to UT. He makes sure he always wears that 2012 national championship ring.” But after that 2019 loss, the world had some other ideas about just how quickly Fields might get another ring.

First, of course, there was the COVID-19 pandemic, which—as with all spring sports—wound up shutting down the 2020 season, with no championships for anyone. Then there was an unexpectedly rocky 2020–21 campaign, with (non-COVID) illnesses and disappointing play. And finally: a not-as-easy-as-it-seemed 2021–22, with identical freakish injuries threatening to cut short Pierceson and Parker Coody’s collegiate careers before they had a chance to write the ending.

“[We] had a lot of adversity,” says Pierceson Coody, before slightly self-revising.

“I say ‘had a lot of adversity.’ Had a lot of adversity for a college golf team.”

“For a college golf team,” Hammer agrees.

That wisdom and perspective is borne out of the maturity, camaraderie, and faith that Fields cultivated in his college golf team … and why they were ultimately able to celebrate on the 18th hole in Arizona. Here’s how the national championship finally happened.

Imagine you’re the Texas football team in the expanded College Football Playoff circa 2024. You knock off the hated Oklahoma Sooners in the quarterfinals. You upset the top-seeded, SEC-champion Texas A&M Aggies (sorry … but just go with it) in the semis. With a pair of wins like those, you’d have to celebrate—and in football, you would get at least a day to do so before getting back to practice for the title game.

But that’s not how it works in college golf. At the 2019 NCAA Tournament, the Longhorns beat Oklahoma in the quarterfinals and Oklahoma State in the semifinals. Both huge wins, and both huge rivals. The Cowboys were not only the Big 12 champion, 2018 NCAA winners, and No. 1 seed, but had also been UT’s competition for the Coodys in recruiting. The Longhorn golfers couldn’t help but be on a huge high. But they also had to tee off against Stanford the very next morning.

“They got the better of us,” says Hammer, the country’s top-ranked amateur that season. “It left a little bit of a sour taste in our mouths.”

The motivation—and the blueprint—for next season was in place.

“We were like, OK. We got beat. It wasn’t what we wanted,” Parker Coody says. “But we’re going to do it [next time]. We’ll be right back there.”

And they were. Soosman was back for his senior year. The two ballyhooed freshmen—Vick (who also starred at football and baseball in high school, and was the nation’s No. 2 golf recruit) and Nome (another young commit, at 13)—already knew each other (as well as Hammer) from Houston, and took their place along the sophomores. “We had the core of our team that was going to be with us for the next three years,” Fields says. “And we were starting to hit on all cylinders.” On March 3, 2020, they were ranked fourth in the country, with two tournaments left before the Big 12 and NCAA championships. And then …

“We were hanging out and joking about how we were going to get a two-week-long spring break,” Parker Coody remembers. “Two days later, Coach is telling us we’re not going to Florida [for the next tournament]. And then a week later: The season’s over. For what happened in the world, it was very minor, but it was crazy how things just stopped.”

For the first few months of lockdown, life was nothing more than Xbox, phone calls, and group texts. But then, as outdoor distanced activity became a safe option, they realized: “We can play golf,” Pierceson Coody says. In fact, everyone wanted to play golf—even high school friends who’d never picked up a club began hitting up the twins, who live on a golf course in Carrollton, Texas, to chip and putt. It also didn’t hurt that The University of Texas has had its own glittering jewel of a golf course in Austin’s Steiner Ranch neighborhood, since 2003—both a convenience and a competitive advantage for the team at any time, not just during a pandemic.

The players could also lean on Fields, whose role as a golf coach is a little different than coaches in less individualized sports—most of his top players have their own private swing instructors and/or putting coaches, leaving him in charge of strategy, team chemistry, and the day-to-day rhythms of competing—and also in charge of each student-athlete’s mind, body, and soul (the entire team, including Fields, holds weekly prayer meetings in connection with the Christian ministry College Golf Fellowship).

“He’s your friend, mentor, mental coach—just so many different things in one,” Pierceson Coody says. “Coach Fields is always just pushing you to be a better person. And a better golfer.”

Looking back, Pierceson Coody sees COVID-19 as another one of those previously mentioned adversities—for a college golf team—that made everybody tougher. Back on campus and the golf courses in 2021, UT had a solid season. Pierceson Coody briefly succeeded Hammer as the world’s top-ranked amateur, holding the spot for one week in mid-April, and was firmly in the mix to win the Haskins Award as the NCAA’s best golfer heading into tournament time. The Horns had a solid third-place finish (once again behind Oklahoma and Oklahoma State) in the Big 12 tournament, with Top 10 individual finishes by Hammer, Pierceson Coody, Nome, and Parker Coody. Then things fell apart in May.

Even as he and Hammer also helped lead the U.S. to a win in the Walker Cup (a collegiate analog to the international Ryder Cup team tournament), and had also already qualified to play in the storied Byron Nelson Open, Pierceson Coody fell ill with a stomach bug. He was bedridden and feverish for the better part of 10 days, and his system still hadn’t recovered when he had to get his second COVID-19 vaccination, which was required to play in the NCAA tournament. He was so weak that he wound up dropping out, and things did not go great for the rest of the team. “We just played terribly,” Vick says of 2021. Ranked sixth in the country before the tournament, they missed the cut in stroke play, finishing 25th. Men’s golf was still one of the nine spring sports that helped clinch UT’s first-ever NCAA Director’s Cup, but the other teams contributed more points.

Still, Texas Athletics Director Chris Del Conte wasn’t worried. “It’s just a one-off thing,” he told Fields. “You’ve got a great team. Go win the national championship the next year.”

So that’s what they did.

But before the triumph, one more Nietzschean—i.e., what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger—setback. This one involved both Coodys, and came out of the very thing that makes them special: an almost dysfunctional will to win.

Whether it’s one of the team’s many games of Ping-Pong or how fast they do homework, “they have an extra gene of competitiveness,” Fields says. “And another when it comes to competing against themselves.”

It was October of 2021, and as a sort of traditional end to the last practice of fall, Fields had his players run a relay race at the indoor athletic performance center below Darrell K Royal-Texas Memorial Stadium—a bit of high-intensity fun “just to kind of gas the guys,” as he puts it.

Pierceson and Parker Coody picked sides as team captains and had planned to take the first leg, but the rest of the golfers insisted they go last—and it became a photo-finish, with the two twins—naturally—an inch apart. Except, there’s no “finish line,” per se: just a padded wall. Normally, you’re supposed to pull up just a little short to touch it at the end. “But they launched themselves into the wall to see who could win,” Fields says. “And they both went down.”

Or, as the ostensible winner, Parker Coody (“I can’t confirm or deny his claim,” Pierceson Coody offers) puts it: “Pierceson and I were being geniuses at team relays.”

“I kind of stumbled into it,” Pierceson Coody says. “Tried to throw my arm into it. My wrist and elbow got stuck underneath me and crunched. And Parker did the same exact thing.”

Fields and the other coaches were right there watching, practically in shock. Fields also holds himself responsible: his players, his race. “But I just could not anticipate that they could lose their competitive minds like they did,” he says.

It turns out they both suffered a fracture of the radial bone, which controls all movement in the palm and wrist. (Yes … the same fracture of the radial bone, in exactly the same place.) As they slogged through rehab and physical therapy, with their teammates helping them take on and off their shirts and shoes and socks, they’d tell the story of the injury, and people would be sure that they were kidding. They could hardly believe it themselves. “You’re a golfer,” Parker Coody says. “You never really expect to break a bone.”

They also didn’t get to hit a golf ball for more than three months. Looking back on it now, Pierceson Coody remembers thinking he might never be the same. “You wonder, am I really going to return to form? Am I really going to be ‘what I once was’? Can I get better?”

Fields sees the identical nature of the Coodys’ injuries as not just twin stuff, but divine providence. And when he told his wife, Pearl, what happened that day, she agreed. “When I went home and I explained it to my wife, she said, ‘Well, that’s a God thing. They’re going to just have to practice their putting and chipping for two months. All they’re going to be able to do is short game.’”

And of course, there was the emotion of it all.

“They came back with a vengeance,” Fields says. “They came back with energy and desire and pent-up anger. It did absolutely 100 percent turn out to be an unbelievable blessing in disguise.”

The Coodys’ absence was also an opportunity for Vick and Nome to assume even bigger roles, and get a taste of the leadership that they’ll be providing as seniors this season. And they were as important as anyone in the tournament.

Pierceson Coody came back even sooner than expected, winning the individual title at Augusta in April by six shots, with the whole team also upsetting then-No. 1-ranked Oklahoma State. At the Big 12 tournament, the Longhorns blew their lead with about four holes to play, finishing third behind Oklahoma State and Oklahoma yet again.

“That was ridiculously painful for everybody, coaches, players alike,” Fields says. “We were in position to win, and we just didn’t finish.”

Fields felt the three seniors were solid but still tight, internalizing all the pressure of their whole UT careers, at the NCAA regionals, which were played in Norman, Oklahoma—a tougher draw than Fields expected. But they were hardly underdogs when it came time for the NCAA Championship in Scottsdale.

After the first couple of days of solid stroke play, things really started to come together. On day three, they had already done well enough that they knew they were going to make the 54-hole cut, and also made the most of playing in the morning. “And that is when the cloud of uncertainty and pressure just absolutely 100 percent dissipated,” Fields says. “We moved into the fourth position in the Elite Eight. And when that happened, the guys were playing the freest golf that maybe they had ever played.”

“There wasn’t a lot said,” Pierceson Coody says. “It was time to be the team that we believed we were. I wouldn’t call it waking up the beast, but it was like everyone’s lights went on and it was time to go play some match play.”

Fields said that last day of stroke play was one of the best rounds he’d ever seen, if not the best that he ever coached. In his eyes, they were the team to beat, even on Arizona State’s home course. “Every round I thought we were going to win, and I think every one of our guys thought they were going to win,” the coach says. “It was almost as if we weren’t even playing in the national championship. There truly was very little pressure for these guys at that point. And it was just simply because they recognized how good they were and how strong they were in their abilities and what they might be able to accomplish.”

Unlike in 2019, “this year we expected to be there, and it felt like everybody knew that we should be there,” Hammer says. “The night before the final match was a much different vibe than it was three years ago. We were pretty locked in. There wasn’t a whole lot of goofing around. We were relaxed, but we knew that the job wasn’t done yet.”

At the start of match play, in the quarterfinals (or Elite Eight), Nome won a key match against Oklahoma State’s Jonas Baumgartner, including what he calls the best shot he’s ever hit, on hole nine. In the semi against Vanderbilt, Hammer had a big win against individual champion Gordon Sargent, making what he calls one of the best shots of his life, a 15-footer from a tough line on the fairway bunker, followed by a horseshoe birdie putt. Against Arizona State in the final, the Coodys both won their matches and Hammer lost his, while Nome got chased down by David Puig after leading before the 16th hole, in a match that wound up in a tiebreaker.

As Nome went on to play the 19th hole (on what was actually hole 10 on the course), the entire crowd stayed on 18 to see if Vick could end it against ASU’s Cameron Sisk. The Sun Devils crowd was pumped, rowdy, and anything but country club, to the point where Vick admitted they were messing with his focus. Fields told him to think back to his time as a high school baseball pitcher, where heckling fans are far more common. Then he shut them up.

Vick led Sisk for most of the match and never trailed, but the two golfers also tied on seven holes, including the 13th, 15th, and 17th. Vick had won the 12th and 14th to go two-up, but Sisk took back a point on 16. With that one-point lead still holding on 18, all Vick needed was to halve another hole. The pressure was on both golfers—Sisk needed a low number just to keep his team alive, while Vick was literally holding the national championship in his hands (and clubs). Vick got to the green in two clean shots, while Sisk had to keep pace from a bunker. With two chances to make a downhill 25-foot putt, Vick instead dispensed with suspense, gently directing the ball just a few inches from the pin, and, with Sisk’s concession, Vick high-fived Fields, threw his white bucket hat in the air and sprinted to Hammer and the Coodys and his other teammates, jumping and whooping and hollering.

For the rest of the golfers, it was almost like the end of a football game, when the defense is on the sidelines watching the offense try to score the winning touchdown, helpless. “It is twice as nerve-wracking watching your teammate play as it is playing,” Hammer says. “But I wouldn’t have wanted anybody else in the position Travis was in.”

Parker Coody says he remembers it like it all happened in slow motion, while Nome, from a distance on Hole 10, tried to figure out whether his tiebreaker would actually make a difference. “I saw [Vick] hit it on the green, so I was feeling pretty safe,” Nome says. Then he and Assistant Coach Jean-Paul Hebert heard a roar. “But since we were 500 or 600 yards away it took a while for the sound to actually build up and get to us. We could see people moving and we thought it was burnt-orange, which was obviously a great sign.”

As for Vick, he had never been more nervous. “Just because you’re playing for your university, you’re playing for your teammates,” he says. “You’re playing for your coaching staff. You’re playing for the alumni. You’re playing for everybody.” But in the end, he says, it came down to instinct. “I just tried to hit that putt as well as I possibly could,” he told Fields.

It all happened for a reason. All the adversities had been overcome. After four years, finally: champions.

And now, at least for the three seniors, professionals. Pierceson Coody and Hammer finished their summer on the Korn Ferry tour, while Parker Coody was on the PGA Tour Canada, and will be looking to be on the PGA tour proper by 2024. Fields has called the trio among the best golfers to ever play at Texas, which is no small thing—both in terms of their collegiate careers and in terms of what those who came before them went on to do. It’s a statement that gives Parker Coody chills.

“He’s seen years and years of great golf come through—for him to say that, he truly does believe it,” Parker Coody says. “It instills a lot of confidence and belief that I can do it. Get to the tour, and one day win on the tour.” Only 17 golfers have won a national championship in Texas. For the Coodys and Hammer to be a part of that elite group is, as Hammer puts it, “pretty special.” And to all be the same age? “It’s just remarkable.”

As they moved from idolizing Tiger Woods and Rory McIlroy as kids to teenagers, their hero was Jordan Spieth, and of course, they also followed Scottie Scheffler. Now? They see their heroes as peers—and rivals. “I know they’ve been through the same process that I’m going through and have been in my shoes,” Hammer says. “I’m doing the same things that they were, so I don’t really have too much of a reason to be starstruck anymore. At this point, I’m trying to beat them.”

CREDITS: Todd Drexler, Justin Tafoya

No comments

Be the first one to leave a comment.