A Life in Magazines: Terry McDonell Donates His Archives to the Briscoe

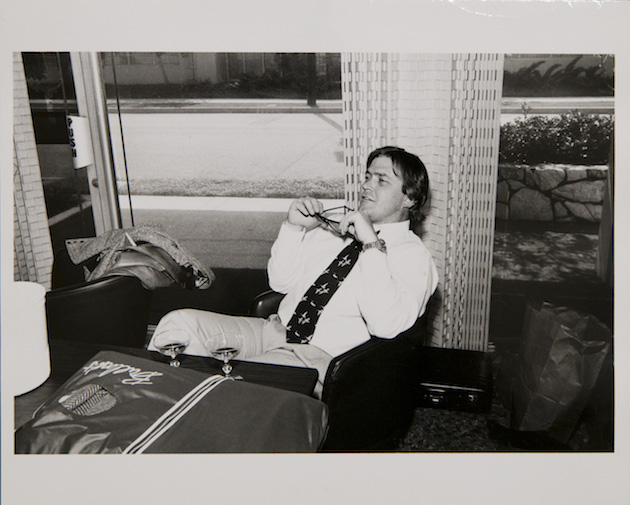

Terry McDonell in the early days of Outside magazine.

New Journalism—the literary style of non-traditional journalism that rocked the magazine world in the 1960s and ’70s—has its share of outsized heroes in writers like Hunter S. Thompson, George Plimpton, and Norman Mailer. But behind many of their enduring pieces of longform journalism is an editor named Terry McDonell. First as founding editor of Outside magazine, McDonell went on to edit magazines like Rolling Stone, Esquire, and Sports Illustrated. Recently, McDonell began compiling his archives—manuscripts, correspondence, personal artifacts, photographs, and more than 1,500 books and magazines he edited—for the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History while simultaneously finishing his memoir The Accidental Life. One recent morning, I interviewed McDonell over pastries at The Driskill. We talked about his career advice for young journalists, and, naturally, the idiosyncratic Hunter S. Thompson.

Alcalde: I wanted to speak with you about your involvement with the Briscoe.

Terry McDonell: The Briscoe is really important to me.

How’d you get involved? How’d you hear about it?

When I was leaving Time Inc. I was trying to decide what I was going to do with all this stuff that I had had forever and [Ransom Center advisory council member] Joe Armstrong told me about the Briscoe Center and about [its executive director] Don Carleton. We had lunch in New York and I listened to everything he was doing and I thought, this is a fantastic thing. All these journalistic verticals, what he had of 60 Minutes and the photography, it was very ambitious and it was way beyond the traditional, very square acquisitions that I saw going on at places like at Cal’s Bancroft or at Harvard, where my son is connected. They’re just sort of dead in the water.

What had happened between the top of New Journalism all the way to digital, all the developments that were coming, the new technologies, from Tom Wolfe to those guys teaching … that’s the arc of my career. And in that arc, no one else was collecting stuff, and no one got that the way Don did. He said, “Well you’ve got all these magazines, maybe there’s a way for us to do something.” And because I had been with so many, it just made complete sense.

The more I learned about the Briscoe and what Don was doing and UT in a more generalized way, the more attractive it all became. The Briscoe Center has a substantial reputation in New York City. You go to those events that Don has when he comes. You see really important journalists together in one place. That never happens other places. It’s a big, big presence in New York.

What are some stand outs in the collection?

I think some of the correspondence is pretty wacky. Some of the stuff with Jann Wenner, some of the stuff with Hunter some of the stuff with Jim Salter. Jean Carroll wrote a book about him and he didn’t want me to talk to her and I just told her I can’t be sources for all you people writing about each other because it will end up very badly for me. You guys are already a big mess among yourselves.

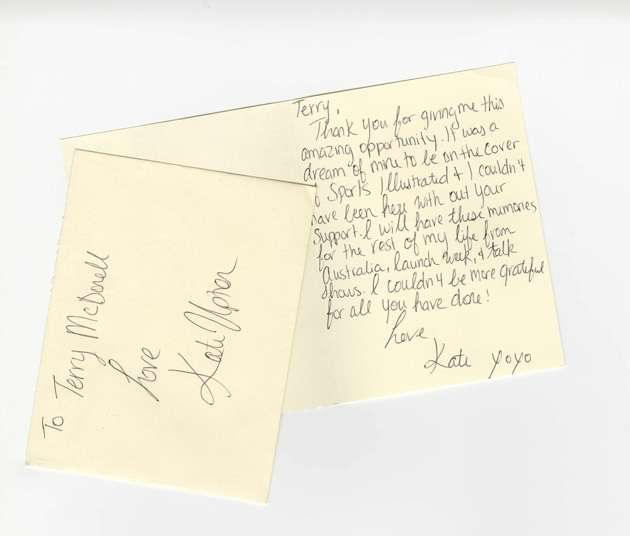

A 2012 letter from model Kate Upton to McDonell upon her first appearance on the cover of the SI Swimsuit Issue.

So there’s a lot of correspondence between those writers and the editor.

Everybody wanted to write about Hunter for a while, so that had to be either deflected or it took a lot of time. You needed a point of view, or a purchase that you could have in the middle of whatever was going on with him. [Laughs.]

How close did you become with Thompson? Was he someone you admired before you got into magazines?

He was a presence from the time I was a very young reporter because that’s when he was doing first the Hell’s Angels and then Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail. I mean I wish he was around now. The closest thing we have to him now is John Oliver. His satire, his ability, by compiling details together to really show the crazy, crazy sides of the Nixon administration but also the McGovern campaign and then Gary Hart, Carter.

Do you think if Thompson was around today he would have taken a TV route like John Oliver or Jon Stewart, or do you think he was a writer first and foremost?

He was a man of his time. The most glamorous thing he could be was a writer and he decided that very early. His son’s middle name was Fitzgerald. He says that he learned to write by typing The Great Gatsby over the whole manuscript, reading it to himself aloud and typing it. I don’t know. Television spooked him. He mumbled—he wasn’t very good at it—but he was a huge presence so you don’t know.

What are some pieces of advice you give young journalists in the book?

The way to deal with an editor is to get to know them. You’ve got to meet them and develop a relationship. You’ve got to make yourself interesting to them. I learned the way all the best writers—like Hunter and George Plimpton—got access, which is the most important thing, is they were just as interesting to the people they were writing about as those people were to them. That’s how they got Muhammad Ali. Hunter would write really funny letters to people like Clinton. James Carvel had that going on with him also.

I got more interesting the more money I made them, but I also tried to be a presence and I would write to them and stay constantly visible. Approaching an editor, you have to figure out how to do that. And the other part is: You have to figure out what you’re going to write about and where you’re going to put it.

- A 2003 National Magazine Award won by Sports Illustrated

- Sports Illustrated’s Sportsman of the Year Award

- 2008 Arthur Ashe Institute for Urban Health Award

The book is called The Accidental Life. What about your life was accidental?

I just moved around so often. I didn’t go on a career path where I worked my way up somewhere. But I didn’t do that necessarily by choice. Either the places I worked went out of business … I got fired once. I always wanted to start my own magazine so I kept trying different things as opposed to a lot of people I worked with really early. But they didn’t get to move around like I got to, and I like that.

Was Esquire one of those jobs that you coveted as a young reporter?

Gee, that was my favorite magazine for as long as I can remember understanding what a magazine was. It was so smart, I thought. Yeah. That was the job I sort of always secretly wanted and then when I got it I thought I would be there forever, and when I was fired I was surprised. Then in retrospect I knew exactly why I was fired: I hadn’t been paying attention … the magazine was OK, but I wasn’t smart about my career or that company or what I was doing.

What was the most difficult piece you ever had to edit?

Some of the big pieces at Sports Illustrated about performance-enhancing drugs were complicated and fraught because it was important not to make a mistake. You could really mess a person’s life up terribly if you were wrong. But at the same time if they were cheating and lying about it, that was not good either. We had to be very careful and methodical about anything that we did.

Not even just their life but their legacy could be tainted.

Yeah. Lance Armstrong. Very hard to edit those stories. He would call on my cell phone and complain that we were getting it all wrong and he wanted me to fire a couple of reporters, that they were lying and had it out for them. Of course he was lying the whole time. But then that’s complicated by all the great work that he did with cancer. That was difficult.

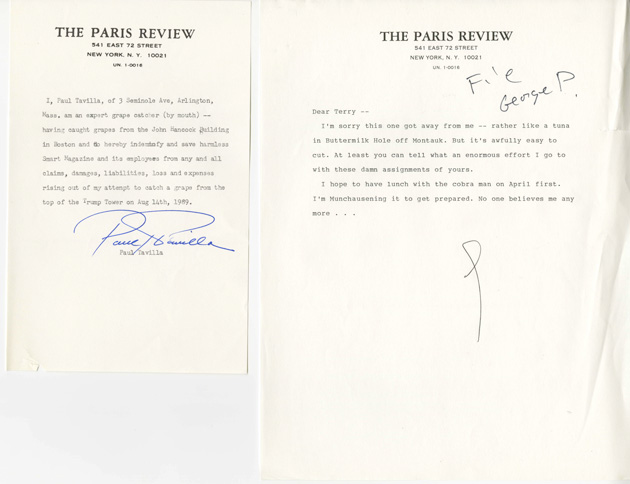

Letters to McDonell from George Plimpton and Paul Tavilla, the grape-catching subject of a Plimpton story.

Are you optimistic about the state of magazine journalism?

No. No. I think that magazines are beautiful objects and some will continue—we’ll always have some—but the time when they were the most important carriers of new ideas has passed. They’re just not fast enough. We consume information in different ways. I mean some of them are still thriving. All the luxury magazines seem to be doing OK … fashion, those are still interesting.

Vanity Fair is still healthy. The New Yorker still is OK, which argues for quality of voice and for the uniqueness of vision of the particular editor, which is more and more undervalued by the people who run the companies who own the magazines. Very few editors sit in the room where decisions are made. There are very few journalists anyway in those companies.

Are you optimistic about writing?

Oh, yeah! That just keeps going and changes and whatever. That’s all great, there’s just more platforms. That’s not suffering. Even longform—there’s more of that than ever.

Yeah, Don Van Natta does the The Sunday Long Read, and that’s popular.

Yeah! And he’s not alone.

So about those other mediums, what is your opinion of those faster platforms people are using to write stories?

They’re all great. I mean they’re all really like appliances. Platforms are appliances to send out and consume. I think my last two years, three years at Sports Illustrated, that’s almost all I did. I wasn’t an editor anymore in the way I had been an editor. I was like a media development executive. I don’t know. But we did the first iPad magazine. They never caught on, but we did the first of those. At one point the swimsuit issue was on like nine different platforms including some wacky PlayStation thing we had come up with.

What would you tell a UT journalism major? Many of them don’t get to stay in the field.

I don’t know. The stories I know are mostly someone who decides they’re going to do something and they go to Afghanistan and they become steeped in it and then they know everything about that and then they become staff writers for The New Yorker or somewhere. You pick up an expertise that is valuable and that expertise could be specifically about a subject matter or your ability to communicate across social media as well and getting a story right for a website. There are a lot of ways to be valuable.

When did you start getting everything ready for the Briscoe?

The same time I was trying to figure out what to do with this book. Those two years were the same two years. I’d be putting things in boxes and sending them here but going through it at the same time. Going through what I had to donate became like an organizing principle for the book. It helped me in a way that I didn’t expect it to.

What was good about Don was that he recognized that I had edited a lot of the people whose papers are over at the Ransom. So my stuff was never going to go to Ransom because I’m not that kind of an artist, but I have all kinds of correspondence with people like Jim Salter and [Norman] Mailer … and they’re all there.

For more info, visit the Briscoe Center for American History.

Photos by Anna Donlan, courtesy the Briscoe Center for American History.

1 Comment