After decades in the trenches,

Charlie Strong

has ascended to the most powerful

job in college coaching.

Now the real work begins.

Teddy Bridgewater should have been happy. In a matter of days, he would be on his way to New Orleans to play Florida in the Sugar Bowl at the Superdome, the biggest game of his college career. But today, surrounded by his teammates on campus at the University of Louisville, he was fuming.

He was about to be named the Big East Conference Offensive Player of the Year following his breakout sophomore season, one in which he had thrown 25 touchdowns in 12 games. He had performed so well, in fact, that it again sparked debate over the NFL’s policy of not allowing underclassmen to enter the draft, with Bridgewater and redshirt freshman Heisman-winner Johnny Manziel at the center of it all. If Bridgewater were allowed to leave after his sophomore season at Louisville, he’d at least be in the conversation for the first pick in the 2013 NFL Draft.1 He was that good, though he wasn’t feeling much love at the moment.

His head coach, Charlie Strong, in an effort to prepare his troops for the matchup against his former team, the University of Florida, was going Gator-by-Gator, delineating how each opposing player would rip through the Cardinals’ offensive line or zip past their defensive backs. As Strong built on this speech, every story—each exaltation of a Florida player—boiled Bridgewater’s blood to the point where he couldn’t contain himself. He sprang up, like he’d just taken a snap from under center.

“Who are you coaching?” the quarterback asked Strong, pointedly. “Louisville or Florida?”

Strong didn’t have time to answer; Bridgewater had already left the meeting room, with a few similarly outraged teammates in tow.

Days later, the two men were hugging midfield as reporters and photographers encircled them. He’d used Strong’s own words as fuel to prove him wrong, willing the Cardinals to an upset, and winning the game’s MVP award in the process.

“After the game,” Bridgewater says, “was probably the best feeling I’ve had in football.”

Strong and Bridgewater immediately after the Sugar Bowl.

ESPN

Looking back, Bridgewater understands what his coach was doing.

“It was amazing,” Bridgewater says of Strong’s Jedi mind trick. “The guys rallied behind me, and we had a great game. That’ll be the approach he takes … his psychological approach to motivate.”

The Sugar Bowl victory over Florida was among the most meaningful in Louisville’s history, and in Strong’s career to date. His Cardinals had beaten a powerhouse, one he’d had a hand in building, on the national stage.

Getting there was the difficult part: He’d won two national titles as Florida’s defensive coordinator; gained tutelage under luminaries like Lou Holtz, Steve Spurrier, and Urban Meyer; and he had nearly 20 years of college football coaching experience while simultaneously interviewing for—and getting rejected from— several head coaching jobs.

Now the successor to Mack Brown, Strong faces the biggest challenge of his—or any coach’s—career. The story of how he got to this moment hits all the touchstones of a feel-good Hollywood tale: the self-starter from a modest background who comes from little money, overcomes discrimination, and wills himself to greatness. It’s what happens next that will determine his legacy.

Strong and his team warm up for the annual Orange-White Scrimmage.

Sandwiched between

the Orange-White Scrimmage and the season opener was the Comin’ On Strong tour in April and May, a 12-city extravaganza that shifted in format nightly, from a sit-down Tex-Mex dinner in Fort Worth (where Strong plainly stated to a stunned crowd, “We will not be in the national championship game”) to a meet-and-greet at the Amarillo Botanical Gardens. There were stopovers as far-flung as El Paso and Beaumont in a seven-day stretch. Strong traveled in a custom burnt-orange bus plastered with images of his face and those of Longhorn players. Parked outside each venue, the bus was flanked by an enormous inflatable Bevo for fans to use as a photo prop.

But the question on every Longhorn’s mind is: Who will start at quarterback?

Tonight, at a beer and hot dogs free-for-all in an upper concourse at Reliant Stadium in Houston, fans won’t learn if it will be the the oft-injured but talented junior David Ash (he requested and received a medical hardship for his concussion-filled 2013 season, thus giving him two more years of eligibility) or raw sophomore Tyrone Swoopes, who will be under center against North Texas on August 30.

But fact-finding isn’t the purpose of Comin’ on Strong. The idea is to introduce Strong to the masses—Texas is, after all, a Longhorn state, right?—and give them a chance to feel close to him. For some fans, even as young as freshmen in college, Mack Brown is all they’ve ever known. Charlie Strong is not Mack Brown, certainly not in the way Brown relished his media time. Gone are the days of the jovial, overlong press conferences and inspirational quotes by the bucketful, though as much as Longhorn fans will miss Brown and his affable personality, they’d surely trade the last few seasons of his enthusiasm for another football made of Waterford Crystal.

He also looks different from Brown. Where Brown was the picture of a traditional college football head coach—your grandfather, if your grandfather had a national championship trophy—at 54, Strong is solid, built like a Brink’s truck. When you look at images of the coach, shaking hands in Amarillo or signing autographs in Tyler, he looks like he could be in front of a blocking sled instead of behind one. He’s ripped. Today, in Houston, the sleeves of his burnt-orange polo look like they are suffering, and every time he grabs at a handful of popcorn from a paper box, I worry they’re about to tear apart. He has a million-dollar smile to go with his twin guns, and he flashes it often. Often doesn’t include when, during his obligatory five-minute media session before the show starts, I ask him about giving Swoopes an earful during the previous week’s Orange-White Scrimmage. Strong isn’t quite pleased with the inference. His eyes quickly meet mine. “We can just stop that,” he says. “I just say what’s on my mind.”

He moves from this quick chat directly to the autograph table, which isn’t slated to open until after his speech is over. Spotting some open time while Longhorn Network personalities hype the crowd, Strong makes his move.

“Let’s get ’em started,” he says to his handlers, sitting down at the table and grabbing a pen. A crowd begins to form in anticipation, and Strong rifles through posters, signing as fast as he can. He’s all business.

That’s not to say he hates doing personal appearances—he just doesn’t love doing personal appearances. Strong fields a question from the crowd: Does he really loathe doing this?

“Even if I do, I can’t really do anything about it, because I have to do it,” Strong says, laughing along with the crowd. “It’s all about us selling our program and the passion and energy in the program. But if anybody ever wants to take over for me, they can come up here and I’ll give it to ’em right now.”

By the time Strong is finished, he appears to have convinced the good people of the Gulf Coast that he has a sense of humor about himself. “The Eyes of Texas” is sung, videos of Justin Tucker’s kick to beat A&M plays, former players take selfies with orange-clad children, and all is right with the Longhorn universe. Tradition is as abundant as popcorn is now strewn all over the carpet, the mighty Earl Campbell bisects the concourse behind a walker, and the vaunted hometown hero Vince Young smiles ear-to-bluetoothed-ear. Everybody has forgotten they ever doubted Charlie Strong.

“Pack your bags. You're going to Florida.”George Baker

“Pack your bags,” Ralph “Sporty” Carpenter said to Charles Strong, who was on his way out of the Caddo Cafeteria on the Henderson State University campus in Arkadelphia when HSU’s head coach approached him. “You’re going to Florida.”

It was the summer of 1983 and Strong, who just months before had landed his first coaching gig at HSU while he worked toward his master’s degree in education, was already headed to the mighty SEC to work for Charley Pell. It was just another graduate assistant position, but the gap between Henderson State and Florida is better represented in light years than the 700-mile flight Strong took to Gainesville the following day. On the new graduate assistant’s arrival, Pell rechristened him “Charlie.”

Strong hadn’t even applied to work in Gainesville; Carpenter had lobbied for the position on his behalf. George Baker4, then an assistant coach at Henderson State, says that Carpenter, who died in 1990, was relentless in his calls to Dwight Adams, then-defensive assistant and special teams guru at Florida, about his new, overqualified employee. Strong had made an indelible impression in less than six months, essentially as an unpaid lackey.

“He was on our staff as a GA, which means he was getting room, board, tuition, and a hell of a lot of work,” Baker laughs. “But he did not stay here a full semester because Coach Carpenter recognized Charlie as being too good for what we were offering him. And that’s when he takes his GA and sends him to Florida because he knew it was better for Charlie.”

If Carpenter is a rare coaching philanthropist, selflessly donating personnel to his colleagues in the big leagues, then his karmic investment has grown exponentially since he shuffled Strong along to Gainesville. Strong was bound for greatness, possessing an indomitable will to succeed, but that’s rarely enough. He needed a push and a guiding hand.

“‘Coach, I ain’t ever been out of Arkansas!’” Baker says Strong told him when he learned of his impending transfer. “Which is not really true, but he had not been around much.”

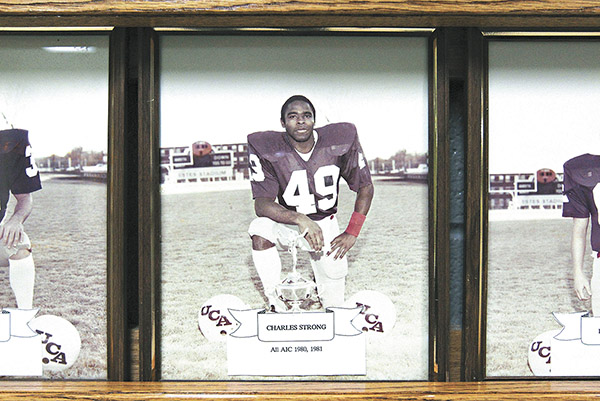

Charlie Strong is

well, physically strong for a coach, but as a walk-on at the University of Central Arkansas in 1980, he was considered skinny and undersized. His scouting report is impossible to reference because there was none. Still formally known as Charles Strong—though known as Rena to his biological family and Tub to his football family—received zero offers as a defensive back coming out of Batesville High in Batesville, Ark. Still, he made the team, leading the Bears in interceptions in ’80 and ’81, and becoming a three-time National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics all-conference safety.

“He is great with people; he is tremendous with players. He doesn’t coddle them, and he solved problems before they got to my desk.”Lou Holtz

It is this notion—take what you’re given and do the most with it—that encapsulates Strong. He wasn’t given the physical gifts (though you wouldn’t think so looking at him now) bestowed upon typical hulking defensive players; he used his speed and instincts to succeed. He didn’t come from football royalty or money—his father Charles was a longtime teacher and high school basketball coach in Luxora, Ark., and his mother, Delores Ramey, and her sister, Cardia, raised their combined 13 children together. He utilized his parents’ work ethic and intellect to earn multiple degrees in education and become a leader of men in his own right. African-Americans aren’t hired as college football head coaches with any sort of regularity: There were a grand total of three in 2005, and only 11 in 2014, less than 10 percent of all FBS head coaches. He toiled for heralded men like Lou Holtz at Notre Dame and South Carolina and Meyer at Florida, waiting in the wings—for too long—to get the chance to prove he could lead an entire team. He does so now without imitation but with evidence of sincere erudition.

“I’ve been around some really outstanding football coaches,” Strong says, “from Steve Spurrier to Lou Holtz to Urban Meyer to Bob Davie to R.C. Slocum. You can’t ever be them, you can only be yourself, but you can always draw something from what they have and use it in a way that it could be very successful.”

The elephant in the room, the legacy he has to live up to, then, is not that of his former teachers, but the beloved coach whom he will follow at Texas, Mack Brown. And that elephant is a fully grown adult and the room is a windowless janitor’s closet. But Strong can’t focus on Brown, not with the pressure of the task at hand: Win football games now. (Though the reverence with which he refers to Brown when asked of his predecessor cannot be ignored: “He’s an icon here. So it’s going to be tough to follow, and it’s hard,” Strong says. “Until I’ve done what he’s done I have nothing to talk about.”) He also must help his players focus in light of recent mediocre-to-passable seasons. Returning upperclassmen are taught upon arrival to spring practice that the past is just that—the past.

“I told them that winning draws a lot of people,” Strong says. “So you gotta win football games. [They’re] not gonna come and watch a bad team play. We have to go play well.”

It’s evident that Strong is playing against more than just the other team. In fact, he already has been for years. Despite accolades from those who know, Strong almost made it to his 50th birthday before a Division I team would toss him the keys to the company car. Universal love poured out of everyone interviewed for this story: already-heralded men playing in the NFL, men who had coached for decades and retired, men in the College Football Hall of Fame. He had played numerous different roles, all of them positive for these men.

He played the stern, fair leader with an inherent sense of initiative. “He is great with people. He is tremendous with players,” Holtz says5. “He doesn’t coddle them, and he solved problems before they got to my desk.”

He proved to be an uplifting, relatable mentor. “He inspired us,” Joe Haden, NFL All-Pro cornerback with the Cleveland Browns, who played for Strong at Florida, says. “He was just a happy dude. I love the way he coaches. He wanted to bring out the best. He made the game fun.”

“If you don’t like Charlie Strong, there’s something wrong with you, not him.”George Baker

He is a salt-of-the-Earth everyman. “The number one thing is his personality,” Bridgewater says. “He connects with all of his players. Every guy on the roster ... every guy from the equipment manager to coaches, players, maintenance people, everyone.”

None of this surprises Baker, who knew him way back when.

“Anybody who gets to know Charlie will say great things about him because he’s a great man,” Baker says, his voice sharpening. “And if you don’t like him, there’s something wrong with you, not him.”

Brandon Spikes’ arrival

at Florida in 2006 was more of an escape than an enrollment. Growing up in Shelby, North Carolina was like the old adage: Get out of town as soon as you can or wind up in a cell or a casket. With his father nowhere to be found and his mother working in a fiberglass plant 12 hours a day, he easily could have fallen prey to illegal activities in what they call “Sheltown” if not for his brother, Breyon Middlebrooks, who taught him how to play football.

In 2003, Middlebrooks was sentenced to life in prison for first-degree murder. By then, a lifetime in Shelby was not an option for Spikes. On his own, he found a mentor in Florida’s then-defensive coordinator Charlie Strong.

“He turned me into a man,” Spikes says. “When I got to school I was older but I was still stuck in my childish ways. He was the first positive father figure I had, other than my brother.”

Under Strong, Spikes became a menacing defender, excelling in tackling and pass defense, and becoming a two-time consensus All-American while anchoring a Strong-led defense that smothered opponents en route to two national championships, in 2006 and 2008.

Spikes may never completely escape the past and the hardships he endured in Shelby, but if Strong taught him one thing, it’s to keep moving forward—through hard work and pragmatism.

“I was one of those guys,” Spikes says, “who liked to mope around and make excuses. He got that out of me at an early age. He always told me what I needed to hear, not what I wanted to hear. He would say, ‘If you want to take the next steps, this is what you gotta do,’ and take me in that direction.”

“He always told me what I needed to hear, not what I wanted to hear.”

Once Strong came on staff at Florida, his trajectory looked upward. Hired in December 2002 as the Gators’ defensive coordinator, Strong was named interim head coach for one game, the 2004 Peach Bowl, after head coach Ron Zook was fired. After the loss to Miami in that game, Florida anointed former Utah coach Urban Meyer, and Strong was the only assistant from Zook’s staff retained. Though apparently some players thought Strong might get his first shot to take the helm at Florida after Zook was axed, the coach himself didn’t feel the same way, telling ESPN in 2012, “I didn’t feel like because of the way we had played that year on defense that I was in any position to say, ‘Hey, I think I deserve a chance at this job.’”

Still, despite his ongoing success and experience under Meyer, Strong couldn’t get a head coaching job, a notion that frustrated him enough to chalk it up to racial discrimination. Strong, an African-American man, is married to Victoria, a white woman. He had heard a lot about disapproving ADs and boosters, but to this point he had dismissed it all as conjecture. Not on a day in January 2009 preceding Florida’s second national title.

“Everybody always said I didn’t get that job because my wife is white,” Strong said during Florida’s media day. “If you think about it, a coach is standing up there representing the university. If you’re not strong enough to look through that [interracial marriage], then you have an issue.”

During the same press conference, Mike Bianchi, an Orlando Sentinel reporter, asked if his interracial relationship caused him to lose potential head coaching positions, including one at an unnamed Southern BCS school whose program was in disarray.

Strong nodded yes. Less than a year later, however, Louisville ignored the noise surrounding him and hired Strong as their 21st head coach, acknowledging the culture of winning he had cultivated, the connectivity he creates with his players, and his tremendous ability to recruit. Tony Dungy, whom Louisiville athletic director Tom Jurich noted had a significant impact on the hire, knew Strong was bound for greatness.

“When they see what he can do,” Dungy said in an interview with ESPN shortly after the hiring was announced, “you’re probably going to have a lot of people disappointed they didn’t hire him sooner.”

At Louisville’s press conference introducing its new head coach, Strong struggled to fight back tears, knowing his moment to lead had finally come.

“When we were offered this job, me and my wife looked at each other and it was so emotional,” Strong said, pausing for a few long beats. “Because you just never thought it was going to ever happen.”

That Charlie Strong is the first African-American head coach in men’s sports at Texas is not lost on the general public—for better or worse. As soon as UT announced the hiring, numerous media outlets praised athletic director Steve Patterson for searching beyond the good ’ol boys of Saban, Briles, and Gruden.

Strong’s race also had no bearing internally, according to Patterson, who says, “We just tried to hire the best damn football coach that [we] could. It happened to be that he is African-American. I didn’t set out trying to make a political statement.”

Was he conscious it would make waves, though?

“Oh God no.”

It did.

Strong’s ascension to arguably the top coaching position in college sports was met with detraction—ranging from outright racist to low-level trolling. Burnt-orange shirts bearing Strong’s face and the racist message “Black is the New Brown” popped up in an Etsy store and the Dallas Morning News tweeted the headline “Why [Charlie Strong] is not a hip-hop coach.”

On the purely outraged-because-it’s-UT side, longtime booster Red McCombs, ’48, Life Member, Distinguished Alumnus, felt like the hiring was made in haste and fell short of the caliber of coach this prestigious position could endow. Describing the process to ESPN 1250 radio, he said the process of Strong’s hiring felt like a “kick in the face.”

After the annual Spring Game, the website IMissMack.com appeared, selling shirts and wristbands guaranteed for delivery in time for the season opener against North Texas.

By now, most of the dissent has diffused. The T-shirt was yanked (it was never confirmed if it was the work of a UT fan) and the Dallas Morning News deleted the tweet. McCombs personally apologized to Strong (who responded that no apology was necessary) and to the public, saying, “[Strong] wanted my help and my support. I told him I’d be happy to do it.” The two men are now close. IMissMack.com is still online, though is merely the work of one idle individual and has been more or less met with unilateral derision on social media.

In January, after Strong had settled in a bit, a source close to the team relayed information from meetings Strong conducted with his players and coaching staff to Barking Carnival, a popular UT-centric sports blog, unveiling 11 expectations for the young men. The list included rules like earned off-campus living privileges; a ban on earrings, drugs, stealing, and guns; a reminder about treating women with respect; and a third missed class leading to your position coach running laps (“The position coaches don’t want to run.”). The memo, though not official, caused a different type of stir in Longhorn Nation: a positive one. While there were some naysayers, the 650+ comments mostly consisted of an outpouring of support for tangible guidelines and signs of a culture change. Strong has already put his money where his mouth is: At press time, eight players have been suspended for infractions, with two, Kendall Sanders and Montrel Meander, permanently removed from the team for alleged sexual assault.

All along, Patterson has balked at any doubt about Strong’s ability to lead Texas back to glory.

“I don’t worry about sports talk radio or yammering on Internet,” he says. “My job is to evaluate talent and try to make best decision we can.”

On the idea that Nick Saban’s folks were gassing up a private jet between Tuscaloosa and Austin regularly, and that Art Briles would have taken the Texas job had he been able to skip the interview process, it’s just more noise.

“It’s the job of an agent,” Patterson says, “to lie all day long every day to try to create the impression that something is happening and create a favorable outcome for that client.” The process, then, wasn’t the total anarchy that Orangebloods.com or Barking Carnival would have Longhorn Nation believe.

"I knew I was coming to ... an institution with a lot of pride and a lot of tradition."Charlie Strong

“Of course when you read the papers,” Patterson says, “it’s going to look chaotic. It’s to be expected. Having said that, what you read in papers or on blogs—which are more useless—doesn’t bear any relationship to what’s happening in reality.”

Strong is well aware of the racial issues and tensions he’s faced on his long ride to the top, but he doesn’t think about his legacy in terms of black and white.

“I never looked at it as, ‘Hey, I’m going to Texas to be the first black head football coach.’ I knew I was coming to an outstanding program with a lot of resources, great academics, great athletic facilities, and an institution with a lot of pride [and] a lot of tradition.”

The greatest coaching job in college football is even better if it breaks a barrier—not that Strong set out specifically to do that at UT—and only enhances his legacy. He’s gone from a young man who just wanted to play college sports and maybe become a teacher like his dad to one of the most powerful coaches in the NCAA.

“Well I know it won’t go unnoticed just because of skin color, but you really gotta look at it like this: You’re just a good football coach, and the color doesn’t matter because at the end of the day you still have to go win football games,” Strong says.

"You’re just a good football coach, and the color doesn’t matter because at the end of the day you still have to go win football games."Charlie Strong

No matter what happens with Charlie Strong in his first year at Texas—a 5-7 season rife with injuries or an undefeated season culminating with a dismantling of Alabama in January 2015—the narrative will likely remain the same. Charlie Strong was hired based on merit, and if—God forbid—he’s fired, it will be because of dismal results. Even if Strong won’t affix this broken barrier to his own legacy, he acknowledges the effect it will have for others in a similar position.

“You have an opportunity to touch so many people’s lives because there are a lot of African-Americans hoping, and they’re looking at your work and hoping someday they could aspire to be like you.”

On a surprisingly mild day

in mid May, Strong’s schedule is packed to the brim, as it is every day. After his daily five-mile run (“To get some juice flowing and get my mind ready,” he says) Strong meets with the coaching staff at 7 a.m. to come up with a game plan for the day: expectations, vision, and direction for practice. He will then go over notes, meet with the defensive staff separately, watch film, and go out recruiting. Some days he meets with the AD (“A couple, maybe three times a week,” Patterson says, laughing. “We haven’t had any time to go play golf if that’s what you’re asking.”) This is all before practice begins, when, according to Strong, the hard work starts.

“I tell our coaches all the time, ‘The players are going to practice and they are gonna do what we demand of them.’”Charlie Strong

“I tell our coaches all the time, ‘The players are going to practice and they are gonna do what we demand of them,’” Strong says. “They should be coached each and every second of that day.” It doesn’t always work out that way. Strong—not necessarily a perfectionist, but definitely a coach who wants everything done the right way, every time—isn’t always excited by what he sees, noting, “It’s very rare that everything clicks.”

Haden3 remembers those practices at Florida vividly, and recoils when asked if they resembled a boot camp, as the spring practices were referred to on college sports gossip sites. A post on Burnt Orange Nation from April 24 references the recruiting battle between Texas and Texas A&M hinging on practice, with the implication that some high school players would see Strong’s practices as boot camps, whereas A&M coach Kevin Sumlin allows Aggies to blast rap music and have fun at practice.

“It was no boot camp,” Haden says. “He made it fun, and it was competitive.”

Spikes, who played on the same defenses as Haden and is now with the Buffalo Bills, sees it the same way. “He believes in working hard and putting in work, and it makes the game a whole lot easier,” Spikes says2. “If those guys that are scared to go compete and work hard, they don’t need to be there. If you’re scared of practice and work you don’t need to go [to Texas] anyway.”

Haden agrees, saying: “He made you feel like, ‘Why wouldn’t you go hard for him?’”

Tough work that people actually enjoy—it’s a novel idea. His philosophy is to work hard on weekdays so that Saturday is a breeze.

“When they get to the game,” Strong says, “It’s just so smooth and relaxed and they can let me know afterwards. Practice is much harder than the game. That’s what I like to see happen.”

Repeating the quote Strong made months ago sounds just as absurd now as it did when it first appeared.

“I didn’t even know I made that quote,” Charlie Strong says, and I believe him. He can’t possibly remember every soundbite from the past few months, not with the Longhorn Network interviews, the official pressers, and of course, the monthlong, Texas-spanning tour. “My man, you hear everything, huh? Saying there’s a difference between being mad and being angry.”

“It’s my job,” I say, “to know all of these things.” Plus it was on Twitter.

About the puzzling “I don’t ever get angry, I just get mad” quote that surfaced on the heels of the spring game, Strong can only laugh at what has become the inaugural Coach Strong aphorism.

So what does it mean?

He pauses to laugh again, then comes up with an answer.

“Well, I get mad when you don’t play well. I get mad when a guy doesn’t do what we ask him to do, but I can control that madness. But players understand that—that it’s not that I’m mad at him as a person I’m just mad at what his performance was, where I feel like he could have played a lot better. Sometimes I may snap and get angry, but even if it has to come to where I get mad at a player, I will never talk down to him, and he knows that.”

Bridgewater, with many opportunities to catch the ire of his head coach during his three years at Louisville, says that he and Strong only really butted heads one time. During a tune-up game against Eastern Kentucky in September of last year, Louisville faced a fourth-and-short situation. Strong sent the punt team on the field, but Bridgewater was confused; there were still offensive linemen on the field and the line to gain was mere inches away. So he shooed the punt team off the field and prepared to line up and snap the ball; Strong admonished Bridgewater.

“I waved the punt team off,” Bridgewater says, “and Coach Strong … he just went crazy. [He said] ‘Hey, this is my team!’ It was fun ... it was funny actually. The thing was a misunderstanding, that’s all there really was. All he said was ‘This is my team,’ I said ‘OK, coach.’ I didn’t know what was going on. That was it.”

If that sounds like less than a controversy, it is, even though multiple media outlets reported on the supposed fracas. That’s because it was the only moment of note from the game. Bridgewater went on to throw four touchdown passes and Louisville routed Eastern Kentucky 44-7. And it’s the only time this high-profile quarterback of an FBS team had a run-in with his coach during his entire three years at the school.

To Strong, being angry is holding a grudge, denigrating a player. He doesn’t do that. Heck, he barely reaches his definition of “mad,” if Bridgewater’s story is any indication. That’s how Strong believes in treating players: with discipline where needed, but ultimately with respect. His players respond to that.

Way back in April

Strong declared that Texas won’t win a championship this season, to the chagrin of 800-plus in Fort Worth and a million grumbling diehard fans online. But he isn’t expected to bring home a championship, not after inheriting a team that went 30-21 the last four years and for the first time since 1937 didn’t have a player selected in any round of the NFL Draft.

In fact, of the latter, Strong feels the same way about this anomaly as he does about losses: Don’t look back, don’t mope, just reflect and use the disappointment as motivation to succeed.

“I told our players that it’s just as much their fault as the seniors’ who had a chance to go play at the next level,” Strong says. “Playing in the NFL is an opportunity; it’s not a retirement job, and you have to work at it. It’s all about hard work.”

It also can’t be ignored that three of the players Strong recruited at Louisville—Bridgewater, safety Calvin Pryor, and linebacker Marcus Smith—were drafted in the first round of the NFL draft in May, so he obviously has some goodwill built up in that arena.

On the subject of satisfaction with a specific season outcome, a question Strong has been asked many times since he took the job at UT, he is more abstract, and his non-answer indicates much more than could a declarative “Undefeated!” or “11-1, with a shot at the national title.”

“It’s hard for me to say that because I don’t ever want to put a number on the wins or a number on the losses,” Strong says. “What is going to be successful for me is watching a football team that plays hard, that plays with a lot of passion, a football team that plays together and it plays as a team … y’know, that we can make our fans comfortable to where they will really enjoy it.”

Giving fans a number to feel great about—10 wins, 12 wins—would have been simple enough, but it wouldn’t have been true to who Strong is. He doesn’t set limits on himself and he doesn’t say what people want to hear; he says what they need to hear. It might not happen for Texas this season. In fact, it’s extremely likely that it won’t, even with a new regime in town and some fresh blood on offense, defense, and special teams. But that reality won’t force Charlie Strong to placate the masses. Nor should it. It’s his team.