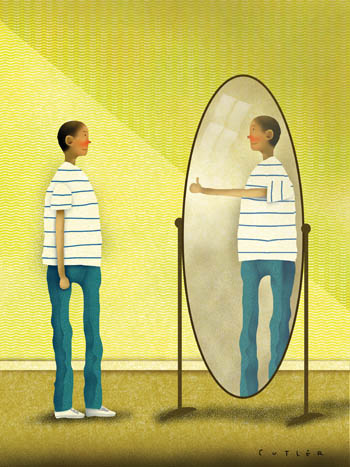

Do Unto Yourself

Self-compassion might be the next big classroom catchphrase.

Illustration by Dave Cutler

If the phrase “self-compassion” sounds a little indulgent, well, there was probably a time when “self-esteem” seemed soft too.

But consider the inroads self-esteem has made into the way young people are educated, as they are taught to feel pride in themselves. With a growing body of research supporting it—some of which is emerging from UT—self-compassion may be the next idea to take hold among educators. The question self-compassion poses is simple: Are you as kind to yourself as you would be to your friends and family?

People who are far harsher on themselves than on others, studies suggest, may be more anxious and depressed, less optimistic or satisfied with life, and less socially connected. Those who are easier on themselves, on the other hand, may derive a host of psychological benefits both in and out of the classroom.

“People think they’ll make themselves soft, that self-criticism keeps them in line,” says UT’s Kristin Neff, an associate professor of human development in educational psychology and a pioneer in self-compassion study. “Actually, people high in self-compassion have less fear of failure. Where does motivation to learn and grow come from? From a willingness to take risks.”

Neff became interested in the subject years ago, when as a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Denver, she worked with leading self-esteem researcher Susan Harter.

Neff had practiced Buddhist meditation to help get herself through a messy divorce, and she started to wonder if self-compassion, with its emphasis on connectedness, might be a perfect alternative to self-esteem.

“Our culture is better at promoting self-esteem, which is all about competition and being better than others,” Neff says. “But narcissism levels have been going up for years,” she says. “That leaves especially youth to expect they’re better than other people. Road rage, bullying—there are lots of unintended consequences.”

Self-compassion has implications for education, Neff says, because unlike self-criticism, it drives intrinsic motivation. That in turn spurs more learning than does the pursuit of grades or the fear of failure.

In one study of UT students published in the journal Motivation and Emotion, those who exhibited self-compassion but didn’t reach their academic goals were more likely to reach for other goals.

For students with clear academic goals—a higher SAT score or better GPA—Neff suggests trying self-compassion by calling to mind a supportive parent. Parents today tend not to strike their children the way they might have decades ago. Instead, they more often encourage and support improvement. Researchers advise students to do the same for themselves.

Read more about self-compassion here.

No comments

Be the first one to leave a comment.