Alumnus Louis Black Reflects on the Festival He Almost Didn’t Start

A quarter-century on, it would be easy for South By Southwest co-founder Louis Black to claim he knew all along just how big a deal it was going to be. But Black, who then was editor of the Austin Chronicle, was skeptical when some of his fellow staffers proposed starting up a music festival.

“In fact, I was very negative and reluctant at first,” Black says. “We were talking about the paper going weekly, and we had no outside funding. We started South by Southwest with the Chronicle’s cashflow, at a time when we didn’t have much. So I was very hesitant. Vehemently opposed, even.”

Fortunately, Black came around to the idea, and he’s been one of the driving forces behind South by Southwest ever since. From its modest beginnings as a regional music conference in 1987, South by Southwest has ballooned into a multimedia powerhouse. Its music, film, and interactive-media conferences attract tens of thousands of people, turning Austin into the center of the cultural universe for one week every March.

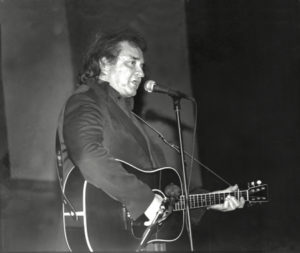

Whatever you’re doing, South by Southwest is the place to show it off. Johnny Cash launched his big comeback at South by Southwest in 1994. More recently, Norah Jones started building buzz there before she won all her Grammy Awards. Newly launched Twitter sees tweets per day more than triple at the 2007 interactive conference. And Kathryn Bigelow’s The Hurt Locker, which won last year’s best-picture Oscar, was the talk of the 2009 film festival.

Whatever you’re doing, South by Southwest is the place to show it off. Johnny Cash launched his big comeback at South by Southwest in 1994. More recently, Norah Jones started building buzz there before she won all her Grammy Awards. Newly launched Twitter sees tweets per day more than triple at the 2007 interactive conference. And Kathryn Bigelow’s The Hurt Locker, which won last year’s best-picture Oscar, was the talk of the 2009 film festival.

Black has been at the center of it all from the start as planner, host, facilitator, and patron of the arts. If it’s hard to define exactly what he does, it’s even harder to imagine him doing anything else.

“At this point, I can’t figure out what else I would do,” Black says. “I’m a publisher, editor, writer, producer, event planner, film-festival executive producer. I can’t imagine being happy doing anything dramatically different because what I do now is a big smorgasbord with every kind of taste I like. I work all the time, but I’d be hard-pressed to tell you what I do because you’re dealing with everything.”

Black’s career story is idiosyncratic, and it should be inspirational to anybody who doesn’t quite fit in. His early years in Teaneck, N.J., were distinguished mostly by dyslexia, attention-deficit issues, tone-deafness, poor math skills, and poorer handwriting. School was “a painful, horrible nightmare,” made worse by the fact that his older sister was the class brain.

“I disappointed my parents and didn’t succeed at anything,” Black says, “because I had no obvious skill set.”

He did, however, begin acquiring a less-obvious skill set that would come to serve him well. At age 12, he befriended Leonard Maltin, who would go on to become one of the most influential film critics in America (Black keeps a copy of Maltin’s most recent movie guide prominently displayed on an end table in his living room).

Bonding over a mutual love of movies, Black and Maltin would go into New York City every weekend to see films, starting with afternoon matinees and ending with late-night features. “Everything from Limey comedies where you couldn’t understand a word to some masterpiece you never thought you’d get to see,” Black says. In the days before the Internet or even VCRs, learning the history of film took this kind of legwork. Before long, Black and Maltin were skipping after-school studies to go watch movies on weekday afternoons, too.

“I wasn’t going to do any better in school, and Leonard wasn’t going to do any worse,” Black says. “So there was a lot of time to watch movies.”

Nevertheless, Black managed to creep into the top half of his high school class by the time he graduated (No. 298 out of a class of 600). That was just enough to get him into college, although it didn’t go well at first. Following “two miserable years” at Boston University, Black transferred to Vermont’s Windham College, where he earned a degree in 1972.

He spent a few years after graduation bumming around the country, crashing on friends’ couches from New Hampshire to Florida before coming to The University of Texas as an English graduate student  in 1975. That didn’t go well, either, until Maltin suggested that Black get in touch with film professor George Wead. At Wead’s urging, Black transferred into UT’s radio-TV-film program in the fall of 1977.

in 1975. That didn’t go well, either, until Maltin suggested that Black get in touch with film professor George Wead. At Wead’s urging, Black transferred into UT’s radio-TV-film program in the fall of 1977.

It turned out to be “totally and immediately life-changing,” Black says. Cultural studies were coming into vogue at universities, and Black had an encyclopedic knowledge of cinema’s less-highbrow side.

“I’d been watching movies for 15 years and I’d seen more cartoons, B-movies, genre films, newsreels, and cult movies than almost anyone else,” Black says. “I had this incredible breadth of knowledge no one else had. I’d always wanted the great college experience where you’d stay up all night talking with friends. I didn’t get that as an undergrad, but I did as a grad student at UT. I went from this schlub to being a star in the class. I felt like a success for the first time, and that tastes much sweeter when it comes later.”

Black thrived at UT, and he was frequently asked to guest-lecture classes in the RTF department. One person who remembers Black from those days is Roland Swenson, who was studying film by day while managing local punk bands by night.

“Louis came and lectured a film-survey class I was taking, about drive-in movies,” says Swenson, another South by Southwest co-founder (and its managing director to this day). “Everybody was breaking pencils trying to keep up with him because he was talking so fast.”

Black also worked with Cinema Texas, programming UT’s student film series, and he wrote a film column for the *Daily Texan — becoming one of Austin’s most recognizable critical voices. That continued after he graduated in 1980 and started up the Austin Chronicle. Black and publisher Nick Barbaro (another Cinema Texas alumnus) were part of a group of founders who launched the Chronicle as a bi-weekly tabloid in the fall of 1981.

Early on, the *Chronicle was just another upstart trying to break into a newspaper market dominated by the *Daily Texan and Austin’s daily paper, the Austin American-Statesman. Black remembers those early years as difficult, bordering on excruciating.

“The beginning was horrible,” Black says. “Cashflow hell. We knew how to write and edit from the Daily Texan, but we hadn’t thought about personnel, distribution, advertising. Nick and I thought we’d get it started and then go somewhere else. It was such a struggle for so long. We were barely holding on. The second year, we wanted out and tried desperately to give it away. But what Nick and I came to realize is that nobody else ‘got’ the paper and what it could be. So we hung in there.”

As the 1980s wore on, the Chronicle established itself as one of the country’s leading alternative papers and an integral community voice on matters both artistic and political. As editor, Black wrote regularly and served as one of the paper’s most visible figures. He also struggled with emotional volatility and an explosive temper.

“The paper was doing better and better, but I didn’t notice because I was in a difficult, hellish place of my own making,” Black says. “I was a mess, constantly freaking out. I was just so scared and cared so much. I quit twice a day for a long time, which is nothing I’m proud of. And if your boss is liable to explode, even if he’s not always doing it, you’re always terrified because you don’t know what will set it off. People should not have to work under those conditions, so I went into therapy. I hope I’m nicer now.”

South by Southwest’s origins go back to the New Music Seminar, a New York-based convention that had started in 1980 and presented showcase performances and panel discussions (plus the attendant networking opportunities). New Music Seminar’s management came to Austin and conducted a series of meetings about doing a regional version of the conference but never followed up.

So the Chronicle’s management decided to go ahead and do its own festival. At the time, it seemed like a risky proposition.

“I knew it was a gamble,” recalls Swenson, who was on the *Chronicle’s staff by then. “The argument that finally won out was that you’re just not respected in Austin until you demonstrate clout outside of town, on a national scale. This could be a way for the *Chronicle to do that.”

It didn’t take long for that clout to build. South by Southwest’s 1987 debut drew 700 registrants, enough to turn a modest profit, and it took off like a rocket. By the early ’90s, it had become the most important convention in America, eclipsing the New Music Seminar (which folded in 1995). The film and interactive-media conferences both started in 1994, only enhancing its stature.

But with that stature has come controversy, and accusations that South by Southwest has gotten away from its grassroots origins and become too big, too mainstream, too corporate. In recent years, T-shirts with slogans such as “South By So What” have become common in Austin. Black tries to ignore the criticism as best he can, but he still feels stung.

“Yeah, you wake up one day and you’re ‘The Man,’” he says, sounding just a tad defensive. “There’s some geological formations people decide you’re responsible for, whether you were or not. There have been a lot of complaints about South by Southwest over the years, but most are hallucinations because there’s no way to solve them. The great myth among struggling young artists is that we’re trying to keep them out of ‘the club.’ The reality is exactly the opposite. Nothing is more exciting than discovering new talent and turning people onto it. When South by Southwest rejects your band, it’s not because we’re evil S.O.B.s rubbing our hands with glee. It’s because you’re not ready. I guess I’m lucky in that I always expected to fail. Whenever I was turned down, I assumed it was my fault, not theirs.”

Whatever the detractors say, throngs still come to Austin every March to partake of “spring break for the music industry.” South by Southwest has become part of the fabric of Austin, in part because it’s an expression of the city’s character. As Black points out, Park City is a ski-resort town before and after the Sundance Film Festival. But South by Southwest is a sampler for what Austin is like year-round, albeit writ large.

“There are a lot of factors,” Black says. “Austin’s a great town, and experiencing barbecue or Mexican food for the first time is amazing. But the biggest overriding factor is that Austin has more cult acts than anywhere else. People decided that coming down to see Joe Ely or Lucinda Williams in a honky tonk in Austin was worthwhile. And over the last decade, as everything has changed in music and culture and communication, we’ve been ideally planted to be part of the dialogue. The interactive-media conference is bigger than the music festival now. And we thought it would be cute to do a boutique film festival. But the timing was perfect, and it’s one of the top film festivals in the world now.”

South by Southwest has been good for the *Chronicle, which upgraded from bi-weekly to weekly publication in 1988. It’s also been good for Black, who has worked on some prestigious projects in recent years. He associate-produced Margaret Brown’s Peabody Award-winning The Order of Myths and executive-produced the 2005 Townes Van Zandt documentary Be Here To Love Me.

Most of his time still goes into the Chronicle, where he remains at the helm, editing and writing. But a healthy chunk of his waking hours also goes toward South by Southwest, especially helping to run the film festival.

“If anybody had told me 20 years ago that South by Southwest would be what it is now, I’d have told them to shut up,” Black says. “I’m so blessed and lucky to have been involved with the work and the people I’ve been involved with. It’s been such a trip. And it’s not over yet.”

No comments

Be the first one to leave a comment.